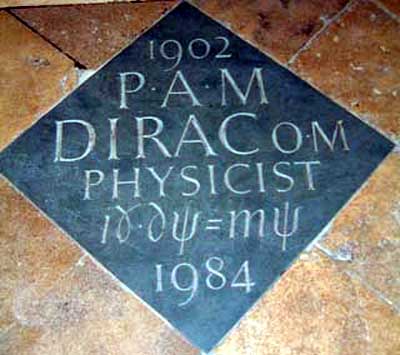

I’ve spoken to various people about simulations over the years. The latest conversation I had was on a Zoom session a couple of weeks ago. We were talking about how Einstein viewed space as some kind of gin-clear ghostly elastic, and how he said a field was a state of space. I was reminded that it would be a good thing if somebody did a simulation to depict things like the photon in this elastic space, along with gamma-gamma pair production, the electron, the positron, and the attraction and repulsion of charged particles. When I say somebody, I mean you, dear reader. Fame and fortune awaits, along with multiple Nobel prizes. Especially since you could easily simulate how gravity works along with how a magnet works, black holes, neutrinos, protons, neutrons, and so on. I say this because a picture is worth a thousand words. Hence a realistic animation is probably worth a million. Which reminds me of another Zoom session I had last week. We were talking about the Dirac equation. It features on the Dirac memorial plaque in Westminster Abbey:

Dirac memorial image from William Straub’s Weylmann.com

Dirac memorial image from William Straub’s Weylmann.com

It’s said to be a “relativistic wave equation” which “describes all spin ½ massive particles”. Unfortunately it doesn’t. The proton is a spin ½ massive particle, but the Dirac equation doesn’t work for the proton. That’s because the proton has a g-factor of 5.585. The Dirac equation works for the electron, which has a g-factor of -2.002, however there’s still an issue. The Dirac equation is said to describe a spin ½ particle like the electron, but it doesn’t describe it at all. If it did, Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac wouldn’t have spoken of the electron as a point particle in 1938, and as a charged shell in 1962. Maths is a vital tool for physics. We can’t do physics without it. We need mathematics for precision and prediction, so we can test our theories, and then improve them. But mathematics is not what physics is, and it’s a mistake to think you can describe an electron with a short sequence of mathematical symbols.

He didn’t pay much attention to the wave in a closed path

I’m not sure if Dirac thought you could. But I’m fairly sure he didn’t pay much attention to the wave in a closed path mentioned in “realist” papers by de Broglie, Schrödinger, Darwin, Born and Infeld, and Belinfante. Maybe it was because Dirac was somewhat autistic. Maybe it was because he supported the Copenhagen interpretation, and went along with Wolfgang Pauli’s spinning-faster-than-light non-sequitur¹. This starts with the classical electron radius of 2.18 x 10⁻¹⁵ m, and says a sphere of this radius would have to be spinning faster than light to generate the electron’s spin angular momentum of h/4π. Sayel Chakraborty explains it on Medium, see The Quantum Quandary: Electron Spin Defies Classical Rotation. Also see page 4 of How Electrons Spin by Charles Sebens. He refers to David Griffiths’ 2005 book Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. Perhaps if I could talk to Dirac, he’d put me straight on all this, and said his equation only describes the behaviour of the electron. I’m not sure. But either way, I would have loved to have cornered him on pair production, the wave nature of matter, spinors, the Einstein-de Haas effect, Larmor precession, the circular motion of electrons in a uniform magnetic field, and all the other evidence that the electron’s spin is real.

Ten thousand physicists have stared at the Dirac equation for almost a hundred years

I don’t know if I would have got anywhere. People can be very resistant to what the hard scientific evidence is telling them. Especially mathematical physicists like Dirac. As far as I can tell, that’s the norm these days. Hence here we are in 2025 when the hard scientific evidence has been around for almost a hundred years, and yet the myth persists that electron spin is some magical mysterious quantum-mechanical “property”. Ten thousand physicists have stared at the Dirac equation for almost a hundred years, and they still don’t know what an electron is. Why do they even give credence to the classical electron radius anyway?

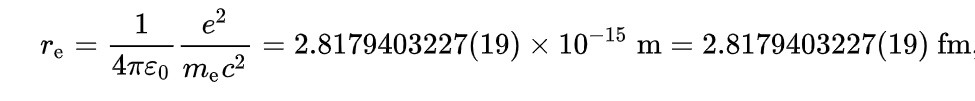

Classical electron radius expression from Wikipedia

Classical electron radius expression from Wikipedia

They don’t have a clear concept of what vacuum permittivity ε₀ actually is. Ditto for unit charge e, and electron mass mₑ. They probably know that 4π is usually associated with a sphere, but do they know that the speed of light c varies in the room they’re in? I think the answer is no. I think they think the electron is a structureless point particle, because that’s what the Standard Model says, and that’s what they were taught when they were young and gullible. So very gullible that they don’t think about the obvious issue: how can the electron be a point particle, when it’s the wave nature of matter? When it’s quantum field theory, not quantum point-particle theory? The answer is it can’t. What it can be however, is an electromagnetic wave, or an electromagnetic field variation if you prefer, in a closed path. Like the quantum realists talked about:

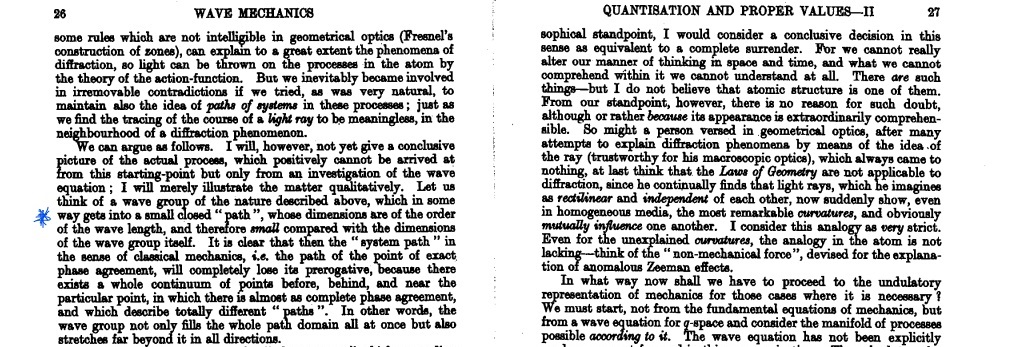

Screenshot from Erwin Schrodinger’s 1926 Quantisation as a problem of proper values Part II

Screenshot from Erwin Schrodinger’s 1926 Quantisation as a problem of proper values Part II

The idea goes way back³, maybe to André-Marie Ampère who talked about tiny magnetic loops of charge in 1823. For myself I think it goes back to 1867 when James Clerk Maxwell said the simplest indivisible whorl would be a worble embracing itself. That was in a letter to Peter Guthrie Tait of Thomson and Tait vortex atom fame. However it was also thirty years before the discovery of the electron by J J Thomson in 1897. He won a prize for his 1882 Treatise on the motion of vortex rings, but the vortex atom went nowhere, and 1897 was almost thirty years before quantum theory got going in the 1920s. The gaps are important, because as far as I can tell, physicists a hundred years ago didn’t know so much about their predecessor’s work. Search Nature on the word worble, and the only hit is D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s A puzzle paper band dating from 1923. He was replying to a previous paper called A puzzle paper band by Charles Vernon Boys. Boys started by saying “Some thirty or forty years ago geometricians were much interested in the endless band of paper to which one half twist had been given before joining the ends”. That’s the Möbius strip.

However it looks like he never read Maxwell’s On physical lines of force

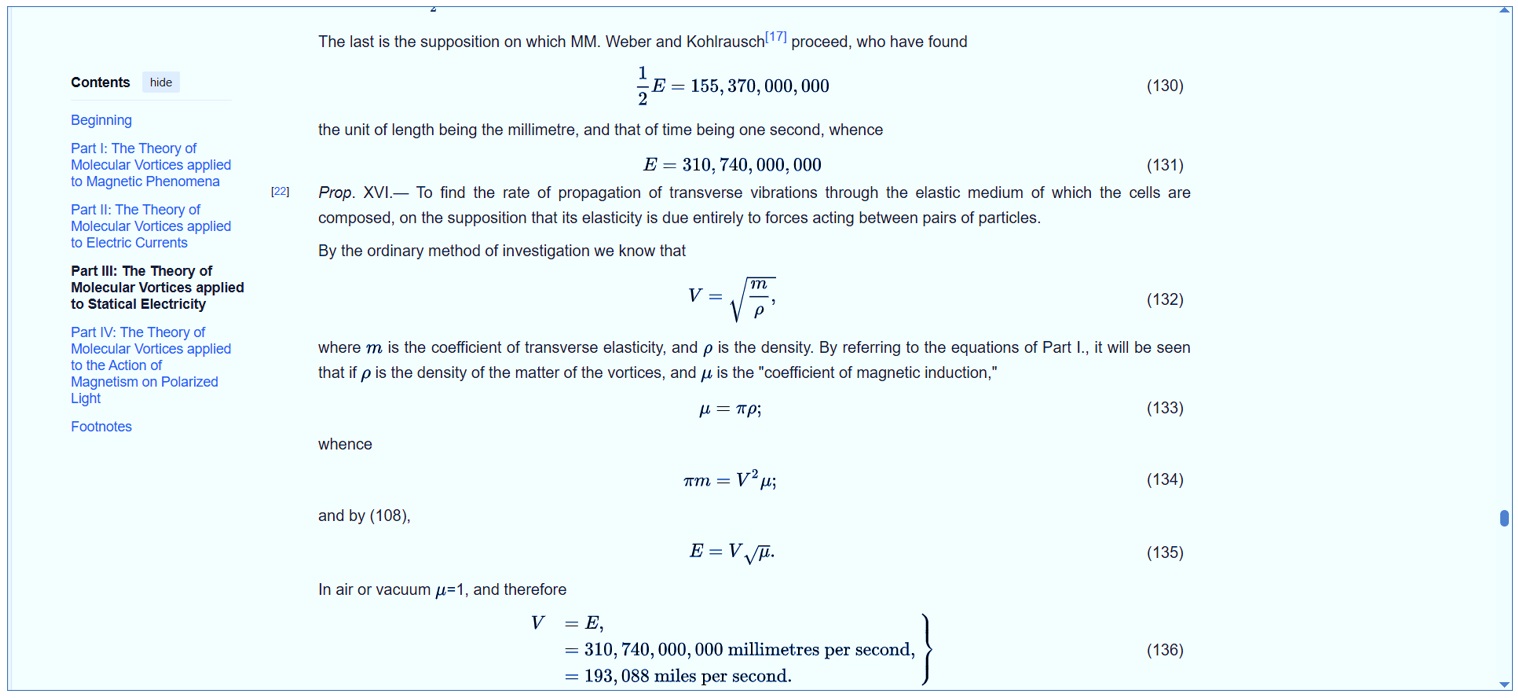

Another example is that Einstein spoke about the speed of light varying in a gravitational field in 1907, 1911, 1912, 1913, 1914, 1915, 1916, and 1920. He also spoke of “the refraction of light rays by the gravitational field”, described space as the aether of general relativity, and said space is the primary thing and “matter is derived from it, so to speak”. However it looks like he never read Maxwell’s On physical lines of force. The subtitle of that is the theory of molecular vortices, and it’s where Maxwell gave an equation for the speed of light. See equation 132. He used Newton’s elasticity equation V = √(m/ρ), and talked of “the transverse undulations through the elastic medium”:

Screenshot from the Wikisource On physical lines of force article

Screenshot from the Wikisource On physical lines of force article

The expression is nowadays given as c = 1/√(ε₀μ₀). This tells me that gravity has an electromagnetic nature, and is a residual force. However Einstein, who had a picture of Maxwell on his wall, spent decades trying to unify electromagnetism and gravity without success. Not only that, but he had a picture of Newton on his wall too. Check out Eric Baird’s year 2000 paper on Newton’s aether model. Baird says Newton attempted to produce a model of gravity in which a gravitational field could be represented as a variation in light speed or refractive index. He also said Opticks was out of print and Einstein didn’t know about it until 1921. Did Maxwell know about it? I think he didn’t. If he had, maybe he wouldn’t have unified just electricity and magnetism, but might have included gravity too. All this is why. if you can simulate electromagnetic waves in space, you can simulate other things too. Things like the nuclear force, dark matter and the mystery of the missing antimatter. It’s all “pure marble” geometry, and simpler than you might think Oh we are so lucky to have the internet. What we’re not so lucky with, is freedom of speech in science. The road to hell is paved with good intentions. Which is maybe why journal editors feel a need to protect the Standard Model. Which is maybe why the late John G Williamson and the late Martin van der Mark² complained to me that they couldn’t get their electron papers published.

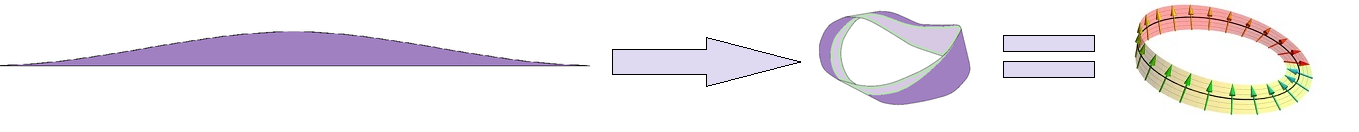

Is the electron a photon with toroidal topology?

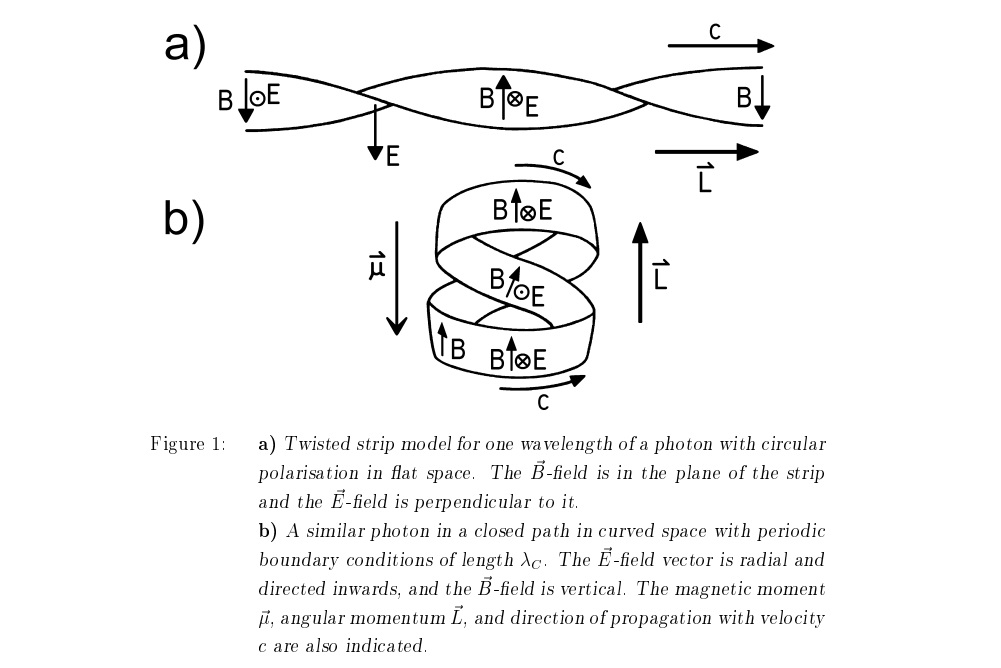

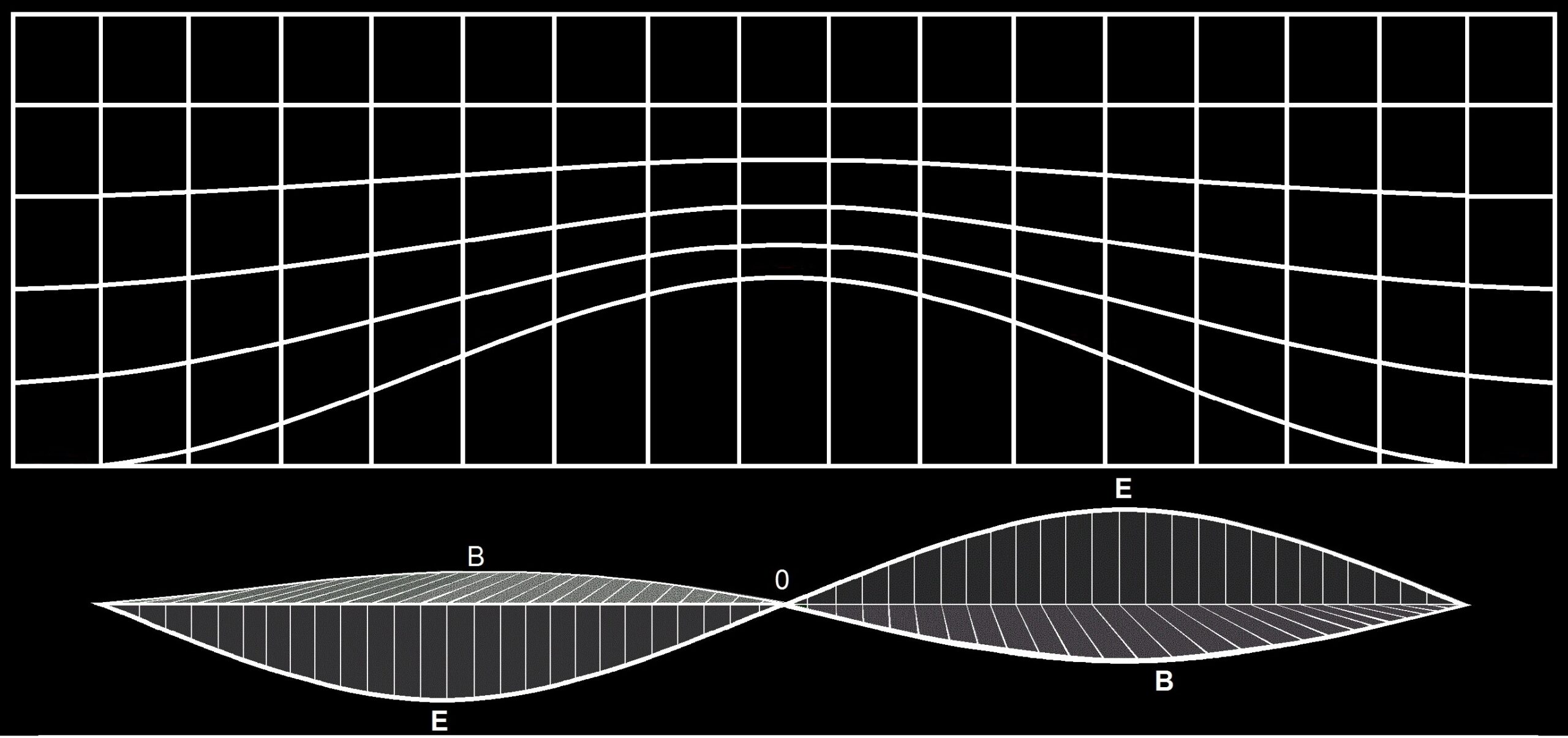

However I feel optimistic about the way things are going. Maybe not in the UK, but elsewhere. People like Musk, Zuckerberg, and Gates are all for free speech now. In addition I’m talking to more and more people who know about Williamson and van der Mark’s seminal paper Is the electron a photon with toroidal topology? They actually wrote this paper in 1991, and it was finally published six years later in a low-impact journal called The Annales de la Fondation Louis de Broglie in 1997. Figure 1 shows a circular-polarized 511keV photon depicted as a ribbon-like twisted strip, followed by the same photon wrapped into figure-of-8:

Image from Williamson and van der Mark’s paper Is the electron a photon with toroidal topology?

Image from Williamson and van der Mark’s paper Is the electron a photon with toroidal topology?

The figure-of-8 latter is associated with Dirac’s belt, also known as the Dirac string trick or plate trick, which is often used to demonstrate spin ½. See for example the 1980 paper Geometric Model for Fundamental Particles by E P Battey-Pratt and T J Racey. In 2009 Jules Moulin said this on Woit’s blog: “They deduced all the details of Dirac’s equation from a few simple topological ideas. They then sent a copy of the paper to Dirac, but unfortunately, Dirac never answered. Racey then turned to other research topics. Only a few scattered people are trying to revive interest in the approach”. Interesting stuff. For myself I love the way Battey-Pratt and Racey said fundamental particles are manifestations of the geometry of spacetime, and the way they referred to William Kingdon Clifford’s space theory of matter. I also love their “vortex spinning in the spherical mode”.

It isn’t how the electron spins

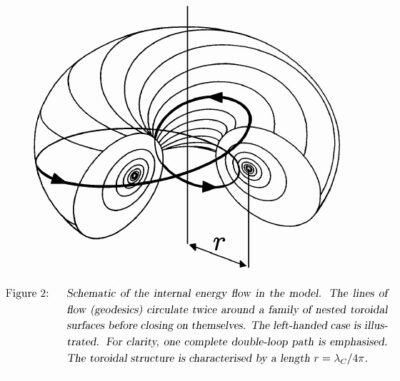

But don’t get bamboozled by “SU(2) double-covers SO(3)”. Go talk to a boy scout or a sailor. The belt trick merely demonstrates that two twists make a turn, and it’s only relevant because twist and turn is what electromagnetism is all about. See Trefor Bazett demonstrating the Dirac’s belt trick with a coffee mug. Watch carefully for the over then the under. Try it yourself, do it fast, and watch the mug. It isn’t weird. It’s a wind then an unwind. It isn’t really two rotations. It’s a shimmy, not a pirouette. It’s a figure-of-8 precession in disguise, and it isn’t how the electron spins. See Williamson and van der Mark’s figure 2 for that. It’s more realistic. It shows you their photon with the toroidal topology. The heavy black line indicates one of many photon paths in “locally curved space”. The rotation is smooth, so smooth you wouldn’t know it’s there. But it is. There’s a minor axis rotation and a major axis rotation, so it goes round twice before it gets back to the same position and orientation:

Image from Williamson and van der Mark’s paper Is the electron a photon with toroidal topology?

Image from Williamson and van der Mark’s paper Is the electron a photon with toroidal topology?

Yes, the torus is more realistic, and it but there’s something missing. You might notice it if you replace Williamson and van der Mark’s ribbon-like strip featuring an electric field E and an orthogonal magnetic field B, with something else. A flat-bottomed sinusoidal strip⁴. That’s when you see how the toroidal photon gives “rise to a real electric charge”.

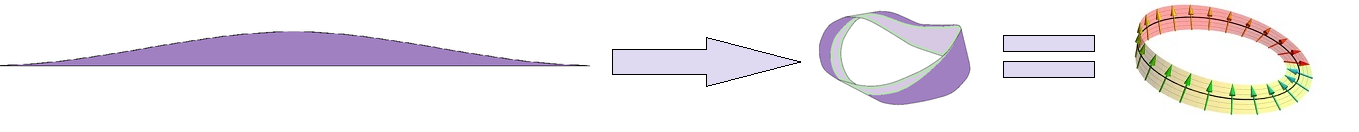

Form the flat-bottomed sinusoidal paper strip into a Möbius strip

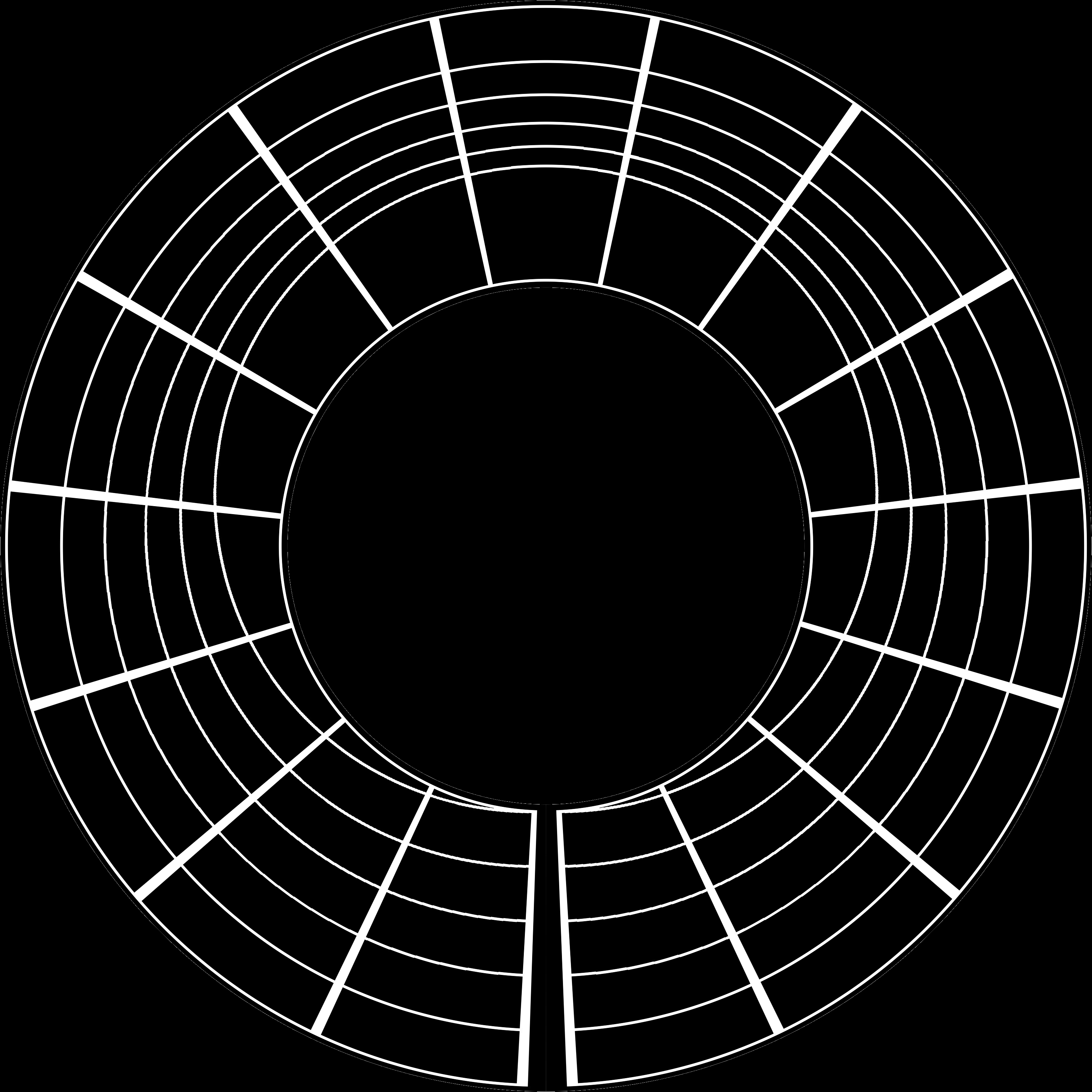

Unlike the Williamson and van der Mark’s ribbon-like strip featuring an electric field E and an orthogonal magnetic field B, the flat-bottomed sinusoidal paper strip represents a wave in the electromagnetic field Fμv. Or an electromagnetic field variation if you prefer. You form the flat-bottomed sinusoidal paper strip into a Möbius strip, like this:

Strip and Mobius images by me, GNUFDL spinor image by Slawkb, see Wikipedia

Strip and Mobius images by me, GNUFDL spinor image by Slawkb, see Wikipedia

I think it’s important that you actually do this yourself. For some strange reason, if you don’t get the hands-on experience, it doesn’t seem to sink in. Three dimensional geometry is like that, human brains aren’t very good at it. So I would urge you to do it yourself. Cut a long thin flat-bottomed sinusoidal strip out of say Christmas wrapping paper, with different colours on each side. Bring the two ends of your flat-bottomed sinusoidal paper strip together. Twist one end by 180°, and then slide the two ends past one another, and keep doing this until the strip is wrapped around twice in a 720° double loop. Then apply Sellotape at various locations around the double loop. You end up with something that looks like one loop, but is really two. It also resembles the typical depiction of a spinor, which is said to be “essential to describe the intrinsic angular momentum, or ‘spin’, of the electron”. Take a look at your Möbius strip. The minima and maxima of the original flat-bottomed sinusoidal strip combine along with all points between to give you something that’s the same width all round. In similar vein the electromagnetic field variation is no longer displaying any sinusoidal field variation. This is why the electron has an all-round electromagnetic field, to which we apply the label charge. It means charge isn’t fundamental, it’s topological. It’s only there because we have an electromagnetic wave wrapped and trapped in its own curvature.

When an electromagnetic wave propagates through space, space waves

Yes, I meant that. When an ocean wave propagates through the sea, the sea waves. When a seismic wave propagates through the ground, the ground waves. And when an electromagnetic wave propagates through space, space waves. There are no waves where something doesn’t wave. And where that something is waving, it is curved. So something else passing through that something will follow a curved path. Get it right, and the wave ends up moving through itself, and the curved path ends up as a closed path. The electron is a spin ½ particle because it’s a worble embracing itself. After that you should think of the Möbius strip as something like a deflated bicycle inner tube, and mentally inflate it so it looks like the toroidal photon. Then you inflate it further, so that it looks like horn torus. Then you inflate it even further, so it looks spherical:

Public domain animation by Lucas Vieira, see Wikipedia commons and the Wikpedia Torus article

Public domain animation by Lucas Vieira, see Wikipedia commons and the Wikpedia Torus article

You have to do this because the electron has no discernable electric dipole moment. See my article on the electron for some other images, most of which are from Adrian Rossiter’s Torus Animations. Also see figure 4 from Hydrodynamics of Superfluid Quantum Space: de Broglie interpretation of the quantum mechanics by Valeriy Sbitnev. But note this: a sinusoidal wave in space has no outer edge, whether it’s moving linearly or on a closed path. So the electron has no surface. It’s not enough to depict the electron as a strip, a torus, a horn torus, or a sphere. The eye of the storm is not the storm.

There’s only one wave there, the electromagnetic wave

I’ll tell you about that, but first I need to say something about the flat-bottomed sinusoidal strip: take a look at the Wikipedia article on electromagnetic radiation and search on the word derivative. You will find this: “the curl operator on one side of these equations results in first-order spatial derivatives of the wave solution, while the time-derivative on the other side of the equations, which gives the other field, is first-order in time, resulting in the same phase shift for both fields”. The derivative of a sine is a cosine. So take the spatial derivative of your sinusoidal strip, and you plot a co-sinusoidal curve that looks like the typical sinusoidal E field variation of an electromagnetic wave. Take the time derivative of your sinusoidal strip, and you plot a co-sinusoidal curve that looks like the typical sinusoidal B field variation of an electromagnetic wave. These are usually depicted as two orthogonal in-phase waves, but that’s the wrong picture. There’s only one wave there, the electromagnetic wave. It’s depicted in the upper portion of the image below. The space and time derivatives are shown in the lower portion:

However the flat-bottomed sinusoidal strip is lacking the photon’s circular polarization. To add this, you have to twist the strip. Twist it by 360°, because the photon is said to be a spin 1 particle, and spin 1 is associated with a 360° rotation. The flat bottom then becomes the centre line of the photon path. Whilst there’s a 180° rotation in the Möbius strip, the photon goes round twice. Check out the Wikipedia article on the spin angular momentum of light. It says the spin angular momentum is ±ħ, which is h/2π. It also say the spin angular momentum is directed along the beam axis, which is the direction of motion, either this → way or that ← way. However that’s only because we use the right hand rule to denote the spin angular momentum direction. If the photon was coming towards you, the rotation would be like this ↻ or this ↺. Don’t worry about the photon spin angular momentum being twice the electron’s, because the electron spin angular momentum of h/4π is only a projection. It’s the spin measured in any given direction, and the electron’s spin is a compound rotation. I presume you can measure it in six orthogonal directions, and in any one direction you see a 6th of the total rotation of 720° + 360°, which is 180°.

The eye of the storm is not the storm

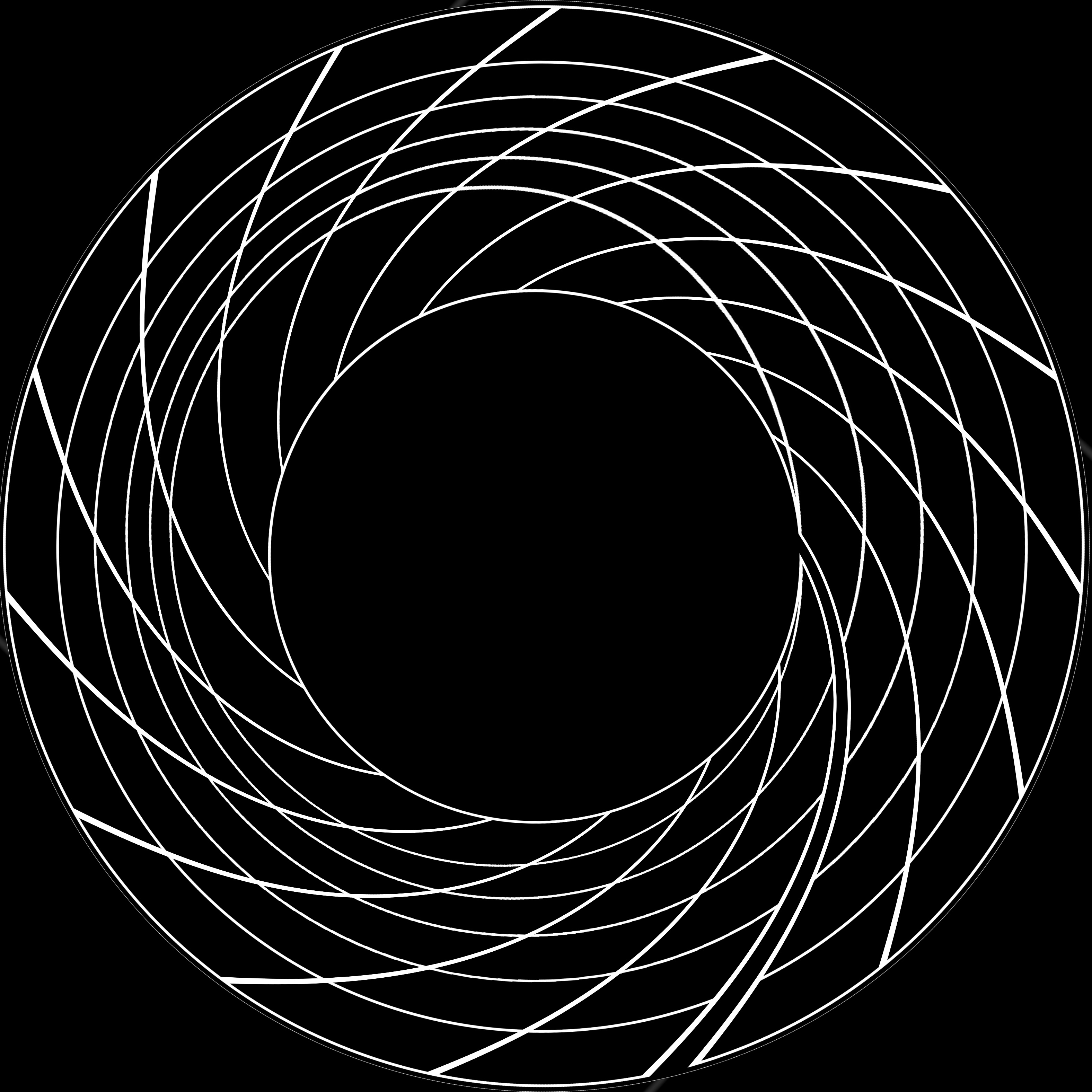

As regards the eye of the storm is not the storm, note that the upper portion of the drawing above depicts a photon in space. The grid lines aren’t really there. They’re only there to show the spatial curvature associated with the photon. The photon location is not just the area under the lowest sinusoidal curve. Whilst this area matches the flat-bottomed sinusoidal strip, the photon location is anywhere where there’s curvature. The curvature diminishes with distance away from the photon path, gradually reducing. It’s similar if you were to wrap the photon into a 720° Möbius configuration. The strip and Möbius images above don’t show this. There’s something else they don’t show. I can bend the photon image into a circle to show you something like this:

Photon image bent into a circle using https://fontmeme.com/bend-images/

Photon image bent into a circle using https://fontmeme.com/bend-images/

This depicts a photon going round in a circle at the speed of light. It doesn’t depict it very well, because the grid lines should extend outwards to fill the whole image, they shouldn’t be circular, and none of the grid lines should be perfect circles because the photon doesn’t have an outer edge. Not only that, but this photon isn’t twisted, it’s a 2D image instead of a chiral 3D image, and there’s only 360° of rotation, not 720°. Sorry about all that. The thing is that all these issues are but mere minutiae compared to the real issue. Which is this: if the inner parts of the photon are going round at the speed of light, the outer parts would have to be going round faster than light. That can’t happen. Light does not move faster than light. The outer parts move at the speed of light, so they lag the inner parts. Like this:

Circular photon image twisted using https://safeimagekit.com/filter/twist-filter

Circular photon image twisted using https://safeimagekit.com/filter/twist-filter

It looks like some of the images you see on spin ½ rotation web pages. Such as on Robert W Gray’s WSM spherical rotations. It’s similar, but not identical. If you know anything about gravitomagnetism, you will recognise this twist. It’s frame dragging. A wave of spatial curvature going round and round with a compound spin ½ rotation gives you a chiral region of twisted space. We call it the electron’s electromagnetic field. This is why I said twist and turn is what electromagnetism is all about. Maxwell and Minkowski didn’t talk about the “screw” nature of electromagnetism for nothing. Why do you think two charged particles move the way that they do? Because each is a dynamical spinor in frame-dragged space, and because co-rotating vortices repel, whilst counter-rotating vortices attract.

The bumpety-bump vanishes, because the minima and maxima of the sinusoidal field variation combine

OK, I hope this is enough to set the scene for a simulation⁵. The first step is to simulate a photon moving horizontally through elastic space. Use a grid or similar to try to depict a twisted sinusoidal wave screwing its way across the screen from left to right. Focus on the middle of your screen and watch the bumpety-bump as the twisted sinusoidal photon goes by. As to how to program it, I’m afraid I don’t know. If you look around the internet, you can find papers like the Maxwell wave function of the photon, but it doesn’t tell you how to simulate a photon. If you can find anything, fine. But if it refers to E or B or a plane wave, I doubt it’s going to help. Anyway, after you’ve got a photon that looks half right, try altering the photon amplitude so that it’s equal to the photon wavelength divided by 2π. Then try sending a left-circular polarized photon towards a right-circular polarized photon and watch for them starting to circle around. If that doesn’t do anything go back to a single photon and make it go round in a circle. Then reduce the diameter of the circle, and keep on reducing it. The photon goes round and round, bumpety-bump, bumpety-bump. However when you get the circle really tight so the photon is in that 720° spinor configuration, something odd happens. The bumpety-bump vanishes, because the minima and the maxima of the twisted sinusoidal field variation combine to yield the same all-round field. It’s a “stationary” wave. It’s still going round and round, but the wave phase is hidden and there’s no discernible wave oscillation, so it looks stationary when it isn’t. A stationary wave is also called a standing wave, even though it isn’t really standing still. Then it’s worth remembering this: standing wave, standing field. The rotation is smooth, so smooth you wouldn’t know it’s there⁶. But it’s there all right. A “spinor” does what it says on the tin.

1 As I speak I can’t find the Pauli original.

2 I met them both, and exchanged emails with them. Martin and his wife Inge even stayed overnight at our house one sunny Saturday. They were well fed and watered, and the conversation flowed.

3 See chapter1 of the 1996 book Geometry of electromagnetic systems by Daniel Baldomir and Percy Hammond. They give a history of electromagnetism, starting with William Gilbert who wrote a book called De Magnete in 1600. They tell us how according to Gilbert “the magnetic force was not a simple attraction but a ‘coition’ which involved rotation”.

4 I don’t know if the photon is at all flat-bottomed. When you twist your flat-bottomed sinusoidal paper strip, the flat bottom becomes the centre line of the photon. That fits with the electromagnetic wave depictions, but I’m not sure it’s right. Oddly enough, I’m more certain about the nature of the electron than the photon. See What is a photon?

5 If it doesn’t work, utmost apologies. If you find something else that does, please do let me know.

6 I forgot to mention: electron mass is just resistance to acceleration for a wave in a closed path. See Martin van der Mark’s Light is Heavy. His co-author was just a little joke, it wasn’t Gerardus ‘t Hooft the Nobel physicist, it was a guy at with a similar name at Philips Eindhoven. PS: Check out Quicycle, which John and Martin set up. Lord rest their souls.

I think a first step would be some 3D animations. I don’t think its ideal to describe something moving around in 3D space with words and 2D images. Like the dynamics of these “knots” of light proposed to be responsible for electrons/etc. It isn’t clear to me whether these knots are supposed to be like a path for an impulse or what. Can the knot itself be rotated, how fast, and so on.

Eg, how would you simulate this with no reason for the twisting and waving?

> depict a twisted sinusoidal wave screwing its way across the screen from left to right

Instead you would animate it.

Malus: yes, you would animate it. Maybe I need to tweak something there to make that clear. Maybe you’d like to do a bit of animating yourself?

I answered your question on Physics Stack Exchange. Here it is:

https://physics.stackexchange.com/questions/505662/why-is-matter-antimatter-asymmetry-surprising-if-asymmetry-can-be-generated-by/841770#841770

That isn’t really my expertise, but it is possible (more likely if theres some funding). But seems like you are describing a situation like this:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=-tO-Bq_VOAk

It may be helpful to first do the opposite of that video, and look at the photon from “heliocentric” (ie, photocentric) perspective. Do we see any twisting/waving if we get rid of the translational motion?

Malus: I like the solar system video, albeit not so keen on the walking droplet video. But no matter, many thanks. Yes, if you got rid of the translational motion you would still see a twisting motion.

If you could draw a few frames of what you expect that would be helpful. Eg, is this wave leaving behind a wake/trail?

Another thing:

> It’s still going round and round, but the wave phase is hidden and there’s no discernible wave oscillation, so it looks stationary when it isn’t.

I guess you don’t like the de Broglie “double solution” (as opposed to pilot waves / bohmian mechanics with point particles), but this once again sounds similar to the strobing/frame rate trick seen at 30 seconds here:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=nmC0ygr08tE

So for the animation, perhaps also consider if there is any averaging/sampling going on. Like are these knots depicting the average of many trajectories, or actually some kind of density/probability distribution at one point in time?

I really like the idea but get stuck when thinking about the details.

Malus: I will draw something. Maybe I will edit it into the article with a suitable note. It isn’t leaving behind any kind of wake.

I don’t have a big issue with de Broglie’s “double solution” (https://fondationlouisdebroglie.org/AFLB-classiques/aflb124p001.pdf), but I would say the central portion of the wave in a closed path is not really a singularity. This reminds me about what I said in the article above: it’s as if physicists a hundred years ago didn’t read each others work. I would have thought they would have come up with some consensus about a wave in a closed path at the 1927 Solvay conference, and played around with Möbius strip. But they didn’t. It looks like it just degenerated into some “you can never hope to understand it” lecture from Bohr and his acolytes, whereafter the realists kind of gave up. Especially when the Nazis got going. There’s a bit of history there I ought to look into.

These knots are depicting the path of a wave in a bulk. There’s a density distribution in the wave, but there is no probability distribution. What we’re talking about here, is a real wave in space. Think about a seismic wave underground, then replace the rock with a gin-clear ghostly elastic space which behaves like a solid.

IMHO the details are simpler than you think. Once you’ve got a handle on it, I think you will really like the idea even more.

Maybe looking head on at a photon (coming at you) itd look something like this: https://youtube.com/watch?v=VRbaBOrqBi4

Anyway, I think thats an easier perspective to start from, after that *then* look at it from an observer perspective.

Forgive me if this has already been mentioned:

.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/7333/7333-h/7333-h.htm

It has, Steve, but thanks anyway. It’s good to see people reading historical papers. There’s some really insightful stuff in them. Like space is a something rather than a nothing, a field is a state of space, and space is the primary thing and “matter is derived from it, so to speak”. I was blown away when I found William Kingdon Clifford’s Space Theory of Matter.

With apologies aforethought I’d like to hijack this thread by asking if there are any calculations that can be made with the frame of reference (pun intended) taught to us by the PD that are more accurate , easier, or just somehow more satisfying than the prevailing way. If so it would get the mainstream attention like a dog to raw meat!🥩🥓🍗🍖

.

PS it might take us a step or two towards those hoverboards!

The closer you’ll get to it are Chantal Roth’s simulations.

Sandra: I couldn’t possibly comment. Apart from pointing out that: it isn’t really two rotations. It’s a shimmy, not a pirouette. It’s a figure-of-8 precession in disguise, and it isn’t how the electron spins. It sure would be good if somebody could help me out here!

Detective: what do you mean? Have you looked at them? The electron IS the “spin”. You can call the phase of the spin a photon or however you like.

The figure of 8 precession is there. The phase of the precession is called the berry phase.

Yes, I’ve looked at them. What I’ve been trying to explain here is that the electron appears to be a sinusoidal electromagnetic wave, a photon, in a twisted double-loop closed path. This can be likened to the Möbius strip used to depict a spinor:

The phase of the photon is somewhat hidden because in this configuration, the minima and maxima of the sinusoidal wave add up to the same value all round. Hence the photon, which is usually a transient electromagnetic field variation passing you by at c, now looks like a motionless all-round standing field. There is no figure of 8 precession here. That’s only there in the ball-and-elastic-connector models that feature a “wind” followed by an “unwind”. The photon phase is however still there, and was revealed by Ehrenberg and Siday in 1949, and rediscovered by Aharonov and Bohm in 1961. A magnetic field is a “rotor” field, it will make an electron go round in circles via Larmor precession, and it will rotate light as per the Faraday effect. So it’s bound to have an effect on the photon in a twisted double-loop closed path. However I feel that the Berry phase was not developed from an understanding of the electron. I should of course actually read Berry’s 1984 paper before saying that. One for another day I’m afraid. Right now, my vegetable plot needs digging.

PS: Sorry to be slow replying. There was an issue with the GoDaddy hosting this morning.

Hi Sandra, Detective,

Here are two implementations of spin 1/2 simulations: https://jsfiddle.net/Chenopdodium/nte9vdyr and https://jsfiddle.net/Chenopdodium/rwnevc6a (select spinor only). There is third one if you like a full blown Unity 3D version 🙂 https://elastic-universe.org/interactive-visualization-software/

It is a bit tricky to summarize briefly yet still correctly :-).

Yes, there is a figure 8 in disguise: if you “watch” how a “grid point” moves over time, it appears to trace two “circles”, like a folded “8”. It is actually not really a “rotation” (it looks like one), but a twisting motion, a harmonic oscillation. It is implemented by using 2 rotation axis that are orthogonal (I use quaternions for simplicity, very easy to use in 3D animations).

I agree that the electron IS indeed the spin (at least one major aspect of it).

When you zoom out, it looks essentially like a (transverse) wave that goes around in circles. Since we use the word photon for travelling transverse waves, I can see why we might just call it a photon that is going in “circles”.

Best wishes, Chantal

Many thanks Chantal. I downloaded the full blown version and ran it. It’s a nice simulation of spin ½ as per Battey-Pratt and Racey.

I find it really interesting that you used quaternions, and that “After Hamilton’s death, the Scottish mathematical physicist Peter Tait became the chief exponent of quaternions”. That’s the Peter Tait that James Clerk Maxwell wrote to in 1867, saying the simplest indivisible whorl would be a worble embracing itself. As for this I’m not sure: “The finding of 1924 that in quantum mechanics the spin of an electron and other matter particles (known as spinors) can be described using quaternions (in the form of the famous Pauli spin matrices) furthered their interest”. But isn’t physics fun!

A mathematical theory is not to be considered complete until you have made it so clear that you can explain it to the first man whom you meet on the street.

.

Hilbert

And by George, I’ve think you’ve got it!

Thanks Steve, but I don’t have a mathematical theory, I have the gist of a theory of everything, and I don’t know how to describe it mathematically. It’s difficult enough to even imagine a wave in three dimensions, let alone a wave in a twisted double-loop closed path in three dimensions interacting with another one. How do you describe that with a line of symbols?

Hey Boss, remember the lab paper I forwarded you ? It has math proofs galore about why quantum knots stay stay together/coherent. And proofs as to why quantum knots do not fall apart/de-cohere.

Their graphics are earily simular to ones you first posted years ago. 👁Farsight 🏴☠️strikes again !!🏁

Yes, Sorry Greg, it was Topologically protected vortex knots and links by Toni Annala, Roberto Zamora-Zamora, Mikko Möttönen. It appeared in Nature in 2022. It started off looking promising because they were talking about Kelvin’s vortex atom, but they didn’t make the leap to the electron and proton. Sorry, I forgot about it. I tend to get a bit overwhelmed with stuff. Which reminds me, I’m supposed to be doing some improved depictions of a photon, and this month’s article. At which juncture the wife is calling me down for tea. Gotta go. Bye!

No worries John.

More importantly: many belated Kudos for sharing such promising info 👏 with the Zoom dialogs! And also that more real life professional physicists/scientists & grad students are active on The Detective !!

So back to The Peanut Gallery I saunder, waiting patiently for the Photon Graphics and further Zoom updates.

Thanks Greg. I’m thinking I must work harder on the “pictorial presentation” side of things. You know, pictures, videos, animations, etc. The more time I spend on all this, the more it occurs to me that the fundamental physics is simpler than people think. However it can be difficult to describe in words, and even more difficult to describe using a line of mathematical symbols. Like I said, a picture is worth a thousand words, hence a realistic animation is probably worth a million. And a Nobel prize. That would be for IT work that really benefitted physics, and really deserved a Nobel prize.

E=mc2🤣

Could Chantal’s program be described as a virtual astrolabe?

.

astrolabe

USA research and development funding may also have to be simulated (NATURE, “Trump’s siege of science: how the first 30 days unfolded and what’s next“).

An interesting article, Dredd. Many thanks.

“it would be a good thing if somebody did a simulation to depict things like the photon in this elastic space” … I send people reading my blog over here to get the quantum details (“The Physics Detective may know”) with a link to your blog.

Many thanks Dredd.

oops … here is the Dredd Blog post where I suggested that The Physics Detective blog is the place to seek answers to certain deep physics questions.

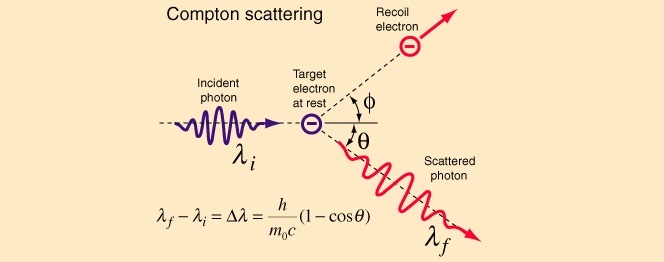

It’s just motion evening out, Dredd. A hot gas is a gas where the atoms or molecules are moving fast. In a solid they’re vibrating fast. A liquid is somewhere between the two. Start a game of snooker with a break for a demonstration. After that, simplify your atom and molecules down to electrons, and check out Compton scattering:

The electron (which IMHO is a photon in a closed path) takes a slice off the incident photon, and is no longer symmetrical, so it moves. If a fast-moving electron were to collide with a slow-moving electron, it would be like an inverse Compton scatter plus a Compton scatter.

“A hot gas” …

Are those events the same in ocean water (salt water)? The referenced post deals with photon saturation (ocean heat content) in the sense of reaching a point where less than the current 90-93% absorption range is diminished some how causing atmospheric heat increase.

BTW the graphs therein simulate historical events prior to 1950 and back to 1900. (That is why I commented here in “guidance for simulations”).

John, may I add that after my prompt in DALL-E “a block of gin-clear ghostly elastic jelly, with grid lines in. You slide a hypodermic needle into the centre of the block, and inject more jelly”, I’ve got pretty nice result. What do you think? I do not know how to post it here, so I posted it on ImgBB (https://ibb.co/N2zQw3vK).

Tony, I love it. A thousand thanks:

Great Scott Tony ! Fabulous indeed !

My aspect of the challenge is to self-teach myself all about A.I. use from scratch. I never ,ever, never, had the need for A.I., so I start from a blank, gin-clear slate.

I’m picked ChatGPT for strictly political reasons, and got a fundamental comprehension of what LaTex,Patent PDFs, PDFs,docx,hmtl, ect……

So, any suggestions from ANYBODY about how to slowly upgrade to proper apps, languages, formats, ect…..? Many thanks Tony & Prof. D.!

Tony,

Thank you for bringing my cubicle into the discussion.

love Dred.

Your article helped me see that Maxwell had already constructed his physical image of electromagnetic waves within an elastic spacetime framework. Crucially, he recognized the need for spin to decouple from space elasticity—and proposed his own conjecture on decoupling manner. Remarkably, this vision remains deeply insightful today. Thank you for illuminating this.

Can you calculate the charge of the electron using the strip model? How Would the calculation be different than that of Williamson and Van Der Mark’s toroidal model?

Sorry, no. I’ve never thought about it actually. Williamson and van der Mark give a figure of 0.91e on page 9 of Is the electron a photon with toroidal topology? The strip model I talk about is essentially theirs but with an electromagnetic field variation as opposed to E and B field variations. Maybe I should look into it. PS: please avoid links to political websites.

Hi Dr P. Detective

This video may be close to what you have in mind. He refers to the Williamson/Van der Mark paper in detail. I’m sure there is nothing here you do not already know, but I found it to be excellent:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hYyrgDEJLOA

Thanks Jeremy. Somebody else told me about the video, and I watched it over the weekend and left some comments. It’s good stuff, well done Huygens Optics. I knew John Williamson and Martin van der Mark, I met them a couple of times, and I have always rooted for their electron model. I refer to it above, and in other articles, such as the electron and A worble embracing itself. What a shame they are no longer with us.

https://medium.com/@mysteron/the-unified-field-as-a-sea-of-dipole-standing-waves-ea5013c2a7fb

This article derives the “Aether” from the initial Universe phase change collapse fully math proved out with PDE’s other paper shows what Alpa is and derives from first princples – all forces can be proven out from this super simple, set up the initial conditions elastic fluid finite mass, finite elasticity, core phase collapse …follow the universe – enforce least action and you get a Universe just like ours.

I’ll take a look Andrew.