When you dig into the history of cosmology, some things catch your eye. Things like the “boundary conditions” in Einstein’s 1917 cosmological considerations in the general theory of relativity. Or something Willem de Sitter said in his 1917 paper On the relativity of inertia. Remarks concerning Einstein’s latest hypothesis. He said this: “if the gμν at infinity are zero of a sufficiently high order, then the universe is finite in natural measure”. There’s also something Paul Steinhardt said in his 1982 Natural Inflation paper. He said this: “We conclude for the Spinodal Universe, that even though the Universe near us is very nearly homogeneous and isotropic, the Universe far away from us (near the edge of fluctuation regions) might be quite different. This is a startling possibility from a philosophical point of view”. Things like this get you thinking. Especially if you’ve heard people say the universe was once the size of a grapefruit.

The universe was once the size of a grapefruit

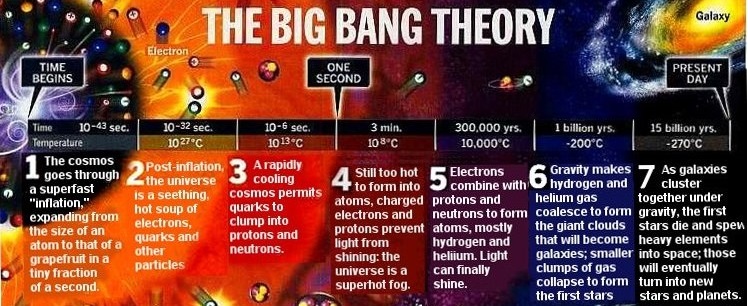

Take a look at the timeline of the Big Bang written by Luke Mastin in 2009. He says “The linear dimensions of the early universe increases during this period of a tiny fraction of a second by a factor of at least 1026 to around 10 centimetres (about the size of a grapefruit)”. This isn’t necessarily true, in that he’s talking about inflation, which is a hypothesis rather than hard fact. But whether it’s true or not, the point to note is that he’s talking about the universe being the size of a grapefruit:

Image by Ed Gabel from The Birth of the Universe: The Kingfisher Young People’s Book of Space, 1998

Image by Ed Gabel from The Birth of the Universe: The Kingfisher Young People’s Book of Space, 1998

He’s also talking about the Big Bang, which is usually thought of as being the beginning of the universe, which is said to have occurred some 13.8 billion years ago. The universe of 13.8 billion years ago is usually said to have been relatively small, and is usually said to have undergone a rapid initial expansion. Whilst we don’t know that every aspect of Big Bang cosmology is totally correct, we are confident that the universe is expanding. And what’s important here is that Big Bang cosmology is talking about the whole universe. The universe is said to have been 10cm across at some point in its evolution. The size of a grapefruit. Not just the observable universe. The whole universe.

The observable universe was once the size of a grapefruit

However if you search the internet for universe size of a grapefruit you tend to find articles like The Three Things Everyone Gets Wrong about the Big Bang by Matt von Hippel. He wrote it in 2014, and he said this: “what do physicists mean when they say that the universe at some specific time was the size of a breadbox, or a grapefruit?” Then he said “it’s just sloppy language. When these physicists say ‘the universe’, what they mean is just the part of the universe we can see today”. But it isn’t just sloppy language. When John Gribbin talked about a universe the size of a grapefruit in his 2008 book The Universe: A Biography, he wasn’t talking about the observable universe. When Marcus Chown talked about a universe the size of a grapefruit in his review of Alan Guth’s 1997 book The Inflationary Universe, he wasn’t talking about the observable universe. When Jeremiah Ostriker and Paul Steinhardt talked about a universe the size of a grapefruit in The Quintessential Universe in SciAm in 2002, they weren’t talking about the observable universe. They were all talking about the universe, the whole universe, and nothing but the universe. I was there, I’m old enough to know they were talking about the whole universe. And I’m old enough to notice that the universe was once the size of a grapefruit has somehow morphed into the observable universe was once the size of a grapefruit. I’ve also noticed that some people who say the latter, say people never meant the former. There’s been some rewriting of history going on, and I don’t like it.

The history

Talking of history, perhaps we should start with Einstein in 1917. He struggled with his boundary conditions, and came up with the “outlandish” idea of a closed curved universe instead. On his 2nd February postcard to Willem de Sitter he said “I am curious to see what you will say about the rather outlandish conception I have now set my sights on”. In 1921 he talked about placing disks on a sphere and how two-dimensional creatures might discover they live in non-Euclidean space. He also said “from the latest results of the theory of relativity it is probable that our three-dimensional space is also approximately spherical”. But in 1932 he and de Sitter dropped the idea in favour of flat space in their Einstein-de Sitter universe. However they said nothing about boundary conditions. Nor was there anything about boundary conditions in Einstein’s cosmology review of 1933: a new perspective on the Einstein-de Sitter model of the cosmos. Indeed our guides Cormac O’Raifeartaigh, Michael O’Keeffe, Werner Nahm, and Simon Mitton say the Einstein-de Sitter model “represented the first well-known open, infinite model”. They also express disappointment that Einstein didn’t discuss the apparent paradox of a matter-filled universe of infinite space. It feels like unfinished business.

The cosmological principle

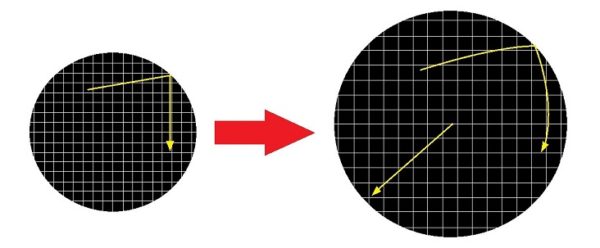

Of course there were other people involved, including Arthur Milne. He’s generally credited with coming up with the cosmological principle which assumes the homogeneity and isotropy of space. See the large scale structure of the universe written in 1980 by Jim Peebles. He tells us Milne referred to the “extended principle of relativity” and “Einstein’s cosmological principle”, and soon fixed on the phrase “Cosmological Principle”. Peebles also tells us the term was quickly taken up and appears in the introductory comments in papers by Howard Robertson (1935), Arthur Walker (1936) and, in a less positive way, Willem de Sitter (1934). I share de Sitter’s sentiment. As it happens I don’t have an issue with the assumption that space is homogeneous on the largest scale, and whilst I have some issues with the universe being isotropic on the largest scale, the homogeneity and isotropy aren’t actually the problem:

Image by James Schombert, see his cosmology lectures including lecture 5 Cosmological Principle

Image by James Schombert, see his cosmology lectures including lecture 5 Cosmological Principle

The problem is that an assumption has somehow been put on a pedestal and elevated to scientific fact. I empathize with Karl Popper on this. He “criticized the cosmological principle on the grounds that it makes our lack of knowledge a principle of knowing something”. It’s like we live in a forest, surrounded by trees, and some dendrologist has come up with the dendrological principal. That’s the assumption of a homogeneous and isotropic forest. The dendrologist might then claim that this means everybody everywhere must see trees all round, and the trees must go on forever, QED. But it simply isn’t scientific to make such claims. We have no evidence to support such assertions.

There is no evidence of any higher-dimensional curvature

Nor do we have any evidence of any higher-dimensional curvature. See the 2001 ESA interview with Joseph Silk for that. The title Is the universe finite or infinite? Silk talks about a universe with an extra dimension, saying this: “To give you an example, imagine the geometry of the Universe in two dimensions as a plane. It is flat, and a plane is normally infinite. But you can take a sheet of paper [an ‘infinite’ sheet of paper] and you can roll it up and make a cylinder, and you can roll the cylinder again and make a torus [like the shape of a doughnut]. The surface of the torus is also spatially flat, but it is finite”. This is akin to the old Asteroids game. If you keep going thataway, you come back thisaway. The surface of the cylinder is said to be spatially flat because if you draw a triangle on a piece of paper and roll it into a cylinder, you do not change the “intrinsic” curvature at all. The angles of the triangle still add up to 180°:

Images by John D Norton, see Einstein for everyone.

Images by John D Norton, see Einstein for everyone.

It’s the same when you then roll up the cylinder into a torus. The cylinder and the torus are said to be spatially flat, but to have an “extrinsic” curvature in a higher dimension. See John Norton’s HPS 0410 Einstein for Everyone course for more, and in particular see his lectures on spaces of constant curvature and spaces of variable curvature. But note this: “if our geometry turns out to be factually one of the curved geometries, then the supposition of a higher dimensioned Euclidean space is a falsehood and a potentially very misleading one”. Quite.

There is no evidence for a closed curved universe

I say that because people have looked for evidence of a closed curved universe, and they can’t find any. See for example Constraining the Topology of the Universe by Neil Cornish, David Spergel, Glenn Starkman, and Eiichiro Komatsu. It dates from 2003 and was reported by Robert Roy Britt as universe measured – we’re 156 billion light years wide! They used WMAP data to look for patterns in the CMBR commensurate with a closed curved “hall of mirrors” universe. They found no such evidence, and concluded that the diameter of the universe was at least 24 Gigaparsecs or 78 billion light years. Somewhere along the line the figure got doubled, but no matter. Cornish used the analogy of compound interest to nicely explain how the universe could get so big in 13.8 billion years, and the paper finished up saying this: “Has this search ruled out the possibility that we live in a finite universe? No, it has only ruled out a broad class of finite universe models smaller than a characteristic size”. The point is that they found no evidence that the universe was closed and curved. Nor did they find any evidence that the universe was infinite. It was similar for the Planck mission. See Planck 2013 results. XXVI. Background geometry and topology of the Universe. The 225 authors concluded that there was no evidence for a universe that had a toroidal topology. Or for any other exotic compact topology. However that didn’t stop the non-sequitur. It only made it worse.

The non-sequitur

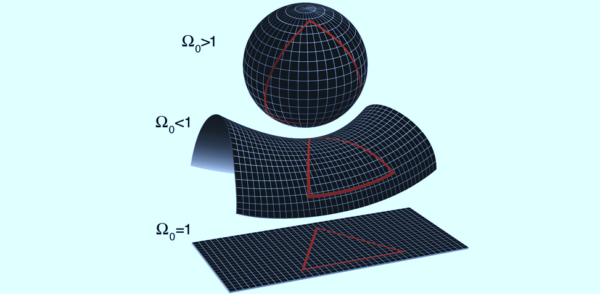

The non-sequitur is in the claim that a flat universe is an infinite universe. Again see the 2001 ESA Joe Silk interview Is the universe finite or infinite? He says this: “So you have two possibilities for a flat Universe: one infinite, like a plane, and one finite, like a torus, which is also flat”. He isn’t the only one saying this sort of thing. See the NASA/WMAP shape of the universe article:

Geometry of the universe public domain image by the NASA / WMAP science team

Geometry of the universe public domain image by the NASA / WMAP science team

It says this: “We now know (as of 2013) that the universe is flat with only a 0.4% margin of error. This suggests that the Universe is infinite in extent”. I’m afraid to say it suggests no such thing. Because the suggestion is based on Friedmann’s 1922 paper on the curvature of space, but space isn’t spacetime, inhomogeneous space isn’t curved space, and expanding space isn’t curved space either. The electromagnetic field is curved space. Friedmann’s paper is based on a confusion between space and spacetime, and on a hypothesis wherein two out of three answers to the shape of the universe were always going to be wrong. And it omits another possibility: a flat finite universe with no intrinsic curvature, and no extrinsic curvature. A universe with an edge.

The mainstream view

Unfortunately a universe with an edge doesn’t feature in mainstream cosmology. Check out Ethan Siegel ‘s 2017 blog article What Does The Edge Of The Universe Look Like? It gives a fairly typical account. Siegel says when you look to greater and greater distances you see smaller newer galaxies because you’re effectively looking further back in time. Eventually all you see is the CMBR. He says what you’re seeing isn’t a boundary in space, it’s a boundary in time. No problem there.

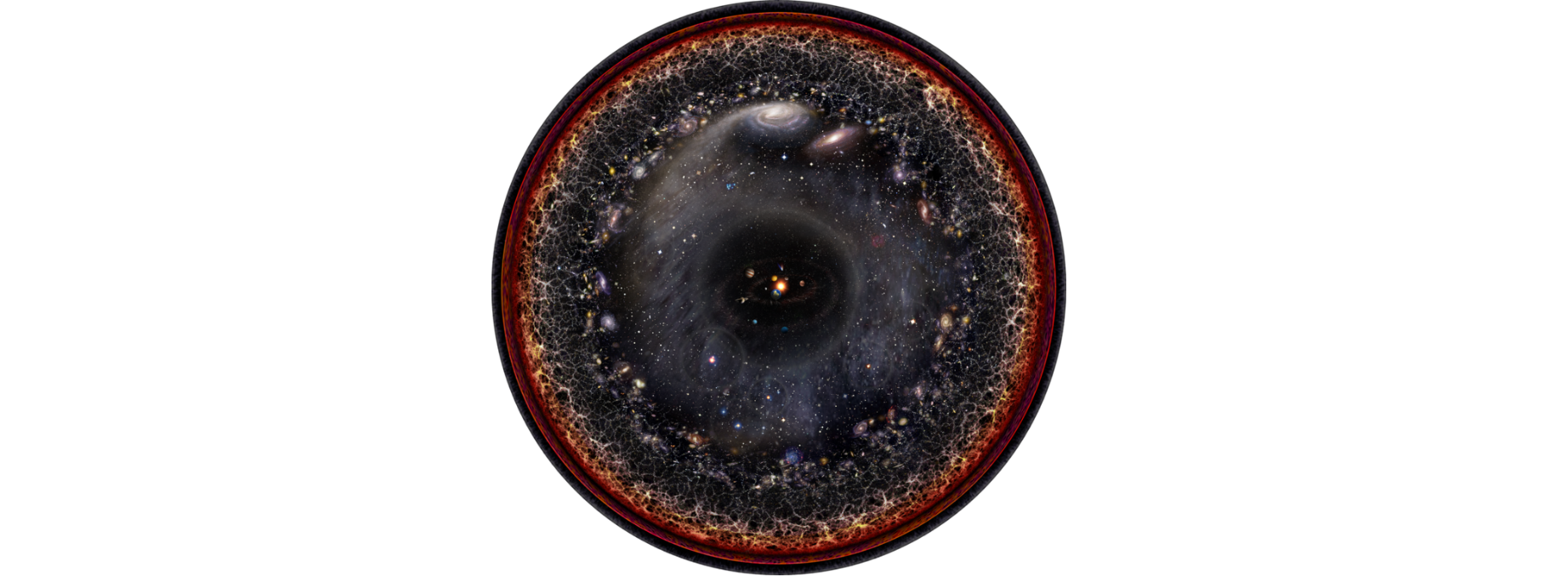

CCASA image by Pablo Carlos Budassi, see Wikipedia Commons

CCASA image by Pablo Carlos Budassi, see Wikipedia Commons

But then Siegel says “any observer, at any location, would see a Universe that was very much like the one we see from our own perspective”. This is taking the cosmological principle too far. As is his claim that the Universe isn’t finite in volume, and that when it comes to the edge of space, there’s no edge at all. Brian Koberlein says much the same in his primeval atom essay dating from 2014. He says to the limits of our measurements the universe has no overall curvature, and that it must therefore be much larger than the region we can observe. Then he says our best understanding of the universe is that it’s spatially infinite. That’s what a lot of cosmologists think, see Erik Høg’s 2014 paper Astrosociology: Interviews about an infinite universe. There seems to be something of a consensus that a flat universe is an infinite universe, despite the Big Bang which is said to have started with a point singularity. Now, I’m no fan of point-singularities because I have some understanding of both black holes and electrons. But I will not swallow the opposite, wherein the universe was infinite when the Big Bang banged, and is even more infinite now. Instead I note Høg’s use of the word sociology. Why, this isn’t just a non-sequitur that contradicts the Big Bang. This is the flip side of the flat Earth.

The flip side of the flat Earth

The story goes that in days of old, people could not conceive of a world that was curved. They could only conceive of a world with an edge. Nowadays we have cosmologists who cannot conceive of a world that is not curved. They cannot conceive of a world with an edge. Chris Baird demonstrates this in his 2016 article Where is the edge of the universe? He says the only way for the universe to be flat and uniform everywhere is for the universe to be infinite and have no edge. He also says the universe started out as an infinitely large object at the time of the Big Bang, and has grown into an even larger infinitely large object. He says this is the most logical conclusion given the scientific observations. I beg to differ. I think it’s taking the cosmological principal too far and treating an assumption like a scientific fact. It isn’t a scientific fact. For all we know some child 46 billion light years away is standing in his garden looking up at the clear night sky wondering why half the sky is black. Or a wall of fire. Or a mirror-image of the other:

Based on the Hubble ultra deep field image courtesy of NASA, see Wikipedia , reflection contrived by me

Based on the Hubble ultra deep field image courtesy of NASA, see Wikipedia , reflection contrived by me

The child asks his father why he sees a reflection in the sky, and his father says “Why my son, don’t they teach you anything in school? That’s the edge of the universe”.

With or without boundary

Unfortunately the edge of the universe isn’t taught in school. Or in college. Or anywhere else. The Wikipedia shape of the universe article has a with or without boundary section. It says this: “Spaces that have an edge are difficult to treat, both conceptually and mathematically. Namely, it is very difficult to state what would happen at the edge of such a universe. For this reason, spaces that have an edge are typically excluded from consideration”. The universe with an edge is excluded from consideration because it’s too difficult. That’s how it’s been since Einstein’s boundary conditions in 1917. Only it shouldn’t be. Because Einstein talked of space as a something rather than a nothing. See his Leyden Address where he described a gravitational field as a place where space was “neither homogeneous nor isotropic”. Also see Helge Kragh’s 2011 preludes to dark energy: “Einstein began to speak of physical space, as described by the metrical tensor gμν in his general theory of relativity, as an ‘ether’”. Kragh tells how Einstein delivered a lecture in 1930 saying space “remains the sole medium of reality”. It’s like Arthur Eddington said in 1934: “There is no space without aether, and no aether which does not occupy space. Some distinguished physicists maintain that modern theories no longer require an aether – that the aether has been abolished. I think all they mean is that, since we never have to make do with space and aether separately, we can make one word serve for both, and the word they prefer is space”. Space isn’t nothing. Waves run through it. A field is a state of space. Nothing isn’t space. Nothing is no space.

Nothing isn’t space, nothing is no space

In the Cosmos article How big is the universe? you can read that perfect flatness would mean the universe is infinite. But you can also read what Guillaume d’Auvergne said in 1231: “The world has no outside, no beyond, since it contains and embraces everything”. That strikes a chord when you combine it with what Einstein said. Einstein said space wasn’t nothing, and his stress-energy tensor likened it to some kind of gin-clear ghostly elastic. Waves run through it. So our universe could be something like a droplet of water with ripples running through it. When those ripples reach the edge of the droplet, they undergo total internal reflection. Note however that there is no outside to this droplet. Also note that the universe is expanding. So whilst a radial light beam is akin to the vertical light beam in a gravitational field, the non-radial light beams aren’t. Instead like the horizontal light beam in a gravitational field, they curve:

They curve because space is inhomogeneous over time. But they don’t have to go on forever, or keep curving until they swing round in some great circle. There’s a third possibility. They could meet the edge. Then they could undergo some kind of total internal reflection, or something else.

There is no place beyond the edge of space

I am reminded of something de Sitter said in his 1917 paper. He said this: “if the gμν at infinity are zero of a sufficiently high order, then the universe is finite in natural measure”. If it’s finite in natural measure there is no place beyond the edge of space. There is no beyond it. There is no more space, and so no place for waves in space to go. So I wonder whether light waves reach the edge of space, and then bounce back. I also look at the Hubble ultra deep field and wonder about the orange galaxy above and right of centre, and the other orange galaxy to the right and down a little. It gets me thinking about halls of mirrors and the edge of space. Perhaps our gedanken observer could float in front of it in his spacesuit, looking at his perfect reflection. Perhaps he could throw a spear and because of the wave nature of matter, see it reflect right back. Perhaps he could jet forward, and perhaps he’d reflect right back too. Or perhaps get turned inside out and back to front. Or into mincemeat. Or into gamma rays. Perhaps he’d suffer a spectacular matter-antimatter annihilation. The edge of the universe might be the ultimate firewall, not unlike Friedwardt Winterberg’s gamma ray bursters and Lorentzian relativity. Of course we don’t have any evidence of some cosmic mirror or a great wall of fire. Perhaps we never will, because perhaps light just stops. Or perhaps it’s none of the above. But we do have evidence of gamma ray bursts. And I think we have evidence for the edge of the universe too.

There is evidence that space is finite

You can trace that back to Sir Isaac Newton. He proposed an infinite universe which avoids gravitational collapse because all stars are surrounded by other stars. It’s akin to Einstein’s cosmological constant, resulting in a uniform potential on the largest scale. A universe that’s in equilibrium “without any internal material forces (pressures) being required”. Only our universe isn’t in equilibrium, because of something akin to Erwin Schrödinger’s cosmic pressure. See Alex Harvey’s 2012 paper How Einstein Discovered Dark Energy. Einstein was in greatest blunder territory whilst Schrödinger was pretty much spot on. Only there’s an issue with that infinite universe. What’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander. It might prevent gravitational collapse because gravitational forces are equally balanced. But it also prevents expansion because pressure forces are equally balanced. If you inflate a party balloon at sea level, it expands as you force air in, then it reaches an equilibrium. The outward pressure is matched by the surrounding air pressure at 14 psi. Ascend to a higher elevation, and your balloon expands as the surrounding air pressure reduces, until it again reaches equilibrium. Take any gedanken sphere of air and it does not expand because outward pressure is counterbalanced by an equal and opposite inward pressure. The same would be true if the atmosphere filled infinite space. Balloons would not expand. In similar vein if space was infinite and it was all at the same homogeneous cosmic pressure, space would not expand. Take any gedanken sphere of space and it does not expand because outward pressure is counterbalanced by an equal and opposite inward pressure. The expansion of space is the evidence that space is not infinite. Perhaps it would help if I showed you a picture.

Let me show you a picture

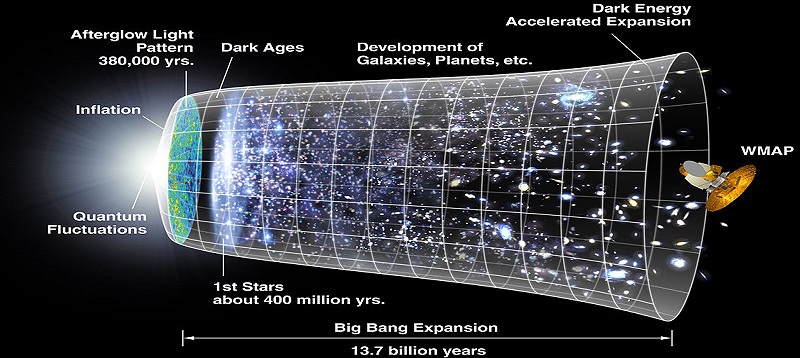

Check out the timeline of the universe article on Wikipedia. There’s a depiction by the NASA/WMAP science team. The description says “size is depicted by the vertical extent of the grid in this graphic”:

Public domain image by NASA/WMAP, see Wikipedia Commons

Public domain image by NASA/WMAP, see Wikipedia Commons

It looks like a champagne flute on its side, without a stem or a base. The time axis goes from left to right, and the diameter increases. Let’s say the real universe is spherical and getting bigger all the time. If you took a slice through the middle every billion years and lined up all your slices left to right like slices of bread, the shape you’d end up with would be like this champagne flute. Every vertical line represents a billion years. And every slice has a size. A real size. I think it’s like Neil Cornish said: “It can be thought of as a spherical diameter is the usual sense”.

Relativity is right

I don’t buy the closed curved toroidal universe. Because we have no evidence for any higher dimensions. And because spacetime curvature doesn’t depend on energy density, it depends on the delta energy-density. If the energy density is the same at every point in space, then expansion apart, light goes straight and spacetime is flat. I don’t buy what Stephen Hawking said either: that if there’s an edge, then we’d have to invoke God. Or what Brian Greene said: “It’s as if that tossed ball shot away from your hand, racing upward faster and faster. You’d conclude that something must be driving the ball away”. No I wouldn’t, because I know how gravity works, and I know that that the ascending light beam goes faster and faster. I also know that the expansion of the universe isn’t repulsive gravity. In addition I will never ever buy the Goldilocks multiverse, where there’s an infinite number of people just like me tippy-tapping away on my laptop. Because I know that Einstein’s general relativity is all about the “dynamic, elastic fabric of reality called space-time”. Which is why there’s a shear-stress term in the stress-energy tensor. Because space can be likened to ghostly gin-clear elastic. And like Schrödinger said, there’s an energy-pressure diagonal too, because space can be likened to compressed elastic. Like a stress-ball squeezed down in your fist. Let it go, and watch it expand. I think space expands in a similar way. And that it’s three dimensional, which means it has an edge, and a centre just like the stress ball. It’s like de Sitter said a hundred years ago: ”the world-matter is the three-dimensional space, or at least is inseparable from it”.

We can never reach the edge

Of course we can never reach the edge of the universe, because the universe is expanding too fast. But next time you stand in the garden looking up at the clear night sky, look to the stars. Out there, someplace, somewhere, maybe somebody can.

What if the universe isn’t as big as we think, or expanding as quickly as we think, because we don’t account for the deflection of light from distant galaxies around mass inbetween, so that it actually takes a longer path, or the lower speed of light when it travels through gravitational fields, so that we overestimate the distance it has travelled?

I’m not sure, Anders. But we can see an awful lot of galaxies out there, so even if the observable universe isn’t 93 billion light years across, it’s still very big. For me the bigger issue is that people say “the universe is flat therefore it must be infinite”.

I agree, I don’t like the idea of an infinite universe either. I can’t see how conservation of energy is compatible with it. You can’t conserve what has no limit. And besides, whenever a model contains an infinity I think it has a problem.

It’s just that I believe that space is what’s constant (except when energy curves it) – a meter is a meter, and c varies depending on the state of space through which light propagates, and in contemporary physics it’s the other way around. So it’s fun to think about what would happen if the paradigm shifted. (Yes, yes, that goes against Einstein, I know. I’m not a scholar, just a seeker of truth. I never liked how speed was chosen as a constant in a theory about relative motion, or how curvature was sold as real.)

Nothing can move faster than light, but gravity affects everything so why should c be an exception.

What if we’re measuring the universe using the wrong time and distance.

I don’t like infinities either, Anders. But I’m not sure space is constant. If it’s expanding, then conservation of energy tells me the spatial energy density must be reducing. Then that tells me the spatial energy must have been very high in the early universe. Like it is in a black hole. That’s a place where the speed of light is zero. Clocks rates are zero too. Which makes me think we are measuring the universe using the wrong time. People say the Big Bang happened 13.8 billion years ago, but where’s the time dilation caused by the high energy density? It’s just not there.

.

Contemporary physics goes against Einstein. The general relativity you read about today features a constant c whilst Einstein talked about a variable c. It also talks about curved space when Einstein talked about inhomogeneous space.

.

When I think of seismic waves, I wouldn’t be surprised if we found waves in space that propagated faster than light

Quite. Given time dilation in the dense beginning, maybe the famous Bang wasn’t such a short, sharp shock (possibly the timeline of the universe looks more like slow and steady inflation than a champagne flute/shuttlecock), and maybe the cosmos isn’t as big as we think… who knows. A variable speed of light is certainly a disruptive idea at any rate.

_ _ _

I wonder if gravitational waves could move faster than light? They are essentially energy waves, not of the electromagnetic kind, but moving in the same medium. Only slightly if at all is my guess.

_ _ _

Thank you John for all your articles! They are extraordinarily well written. Your text is clear and the subject matter, as difficult and complex as it is, becomes simple.

Anders: I’m fairly happy with the expanding universe, but there’s a lot of other things in cosmology I’m not so happy about. Like the presumption of the homogeneity of space in the FLRW metric, or the assumption that dark matter consists of particles, or Alan Guth’s inflation. I’m not so happy with black hole mergers either. But I don’t have so much of an issue with gravitational waves. As for their speed, they’re said to be quadrupole transverse waves, which makes me think they’re travelling at the speed of light. Longitudinal waves typically move faster than transverse waves, and shock waves move faster still. My pleasure re the articles. I try.

Is it possible that asking about the beginning of the universe, it’s size and shape, it’s future etc., is skipping over a preliminary question, and that is whether the universe has given us the tools to answer such problems? Do we know, for example, what tools we’d need, and whether they could be attained?

We need evidence, Tom. There is some evidence. But when it comes to the universe, I’m not sure we’ll ever have enough. Things like gravity are easy compared to the universe.

Oh boy. Will somebody please spare us from this ignorant pontificating crap:

.

http://backreaction.blogspot.com/2021/05/what-does-universe-expand-into-do-we.html

Hmmm? I need a clarification John : if I get ? ants embedded into my pants, is it possible for me to move sideways in time and forward into space ? Would this be considered an example of the inverse square law? Or can I only move forward in time and sideways into space? The only thing I know for certain is if ants ? do get embedded that certain body parts will positively start to shrink and pucker-up away from the local universe………

She’s talking about curvature in some higher dimension and saying “that’s what general relativity tells us”. It doesn’t. Einstein described a gravitational field as a place where space is “neither homogeneous nor isotropic”. The inhomogeneity is not uniform, so if you plot it, you plot a curve. But space is not curved. Yes in 1917 Einstein struggled with his boundary conditions, and came up with the “outlandish” idea of a closed curved universe. But he soon dropped that. See https://arxiv.org/abs/1503.08029 where the authors say the Einstein-de Sitter model “represented the first well-known open, infinite model” of the universe. Hossenfelder is ignored all that and telling her usual fairy tales.

.

No, you can’t move sideways in time. You can’t move forward in time either. Because time is a cumulative measure of local motion. Spacetime models space at all times, so there’s no motion in spacetime. Spacetime is the map, but the map is not the territory. All you can do is reduce your local motion by increasing your motion through the universe. Or relative to me if you prefer, as per the twins paradox. Only now we have the CMBR dipole anisotropy, so we can tell which one of us is really moving.

I finally stumbled thru the link you suggested, thank goodness for the synopses. Long story short, Frau Hossenfelder and numerous others are once again guilty of intentionally/unintentionally omitting the historical facts for their own shortsighted purposes. I guess the pressures of being a money ? grabbing celebrity scientist out weigh the need for accuracy. Constantly keeping the waters stirred and muddy is an excellent way to keep the masses uninformed. A person famously said ” never let the facts get in the way of a good story”.

The pressures of being a money-grabbing celebrity scientist outweigh the need for honesty and free speech too. Try pointing out an error to Frau Hossenfelder and your comment will never see the light of day. Ditto if you tried to post a link to an article like this.

John, earlier you wrote that the early universe was frozen. In a discussion about black holes, somebody asked you – “Inside the event horizon of a black hole… – space…, perhaps energy that is still? Frozen, motionless, energy?” You answered: That’s how I see it. And IMHO, that’s how it was in the early universe.” I have a feeling that you would not disagree with the assumption that beyond the edge of the universe may be this same frozen energy/space. Like an inverted black hole. Would you? Thank you in advance.

Tony: I would disagree I’m afraid. This is tricky ground, the only possible evidence for it is that the universe is expanding. That’s like the flip side of Newton’s infinite universe, which does not undergo gravitational collapse. But I think a black hole is like solid space, where everything is frozen. I also think the whole universe was once like that. In addition I think that beyond the edge of the universe, there is no space. So there is no beyond the edge of the universe. It’s quite a difficult idea to grasp, but I think it helps to think of the German word for space: it’s raum. It means “room”. It’s like the whole universe is one big room. Beyond it there are no other rooms. Beyond it, there is no room. There is no space beyond the edge of space.