Big Bang cosmology arguably started in 1917. Vesto Slipher had measured 21 galactic redshifts by 1917. That’s when Albert Einstein wrote his cosmological considerations paper and Willem de Sitter came up with the de Sitter universe. The next year in 1918 Erwin Schrödinger came up with his cosmic pressure. In 1922 Alexander Friedmann came up with a non-static universe. In 1924 he came up with negative and positive curvature, and Knut Lundmark came up with an expansion rate within 1% of measurements today. In 1927 Georges Lemaître wrote his French paper. In 1928 Howard Robertson wrote his paper On Relativistic Cosmology. In 1929 Edwin Hubble came up with a relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae. In 1931 Einstein conceded that the universe wasn’t static, and Lemaître proposed a primitive atom. Soon Lemaître was talking about the disintegration of the primeval atom and the exploding cosmic egg, suggesting that cosmic rays were the result. The Big Bang was born.

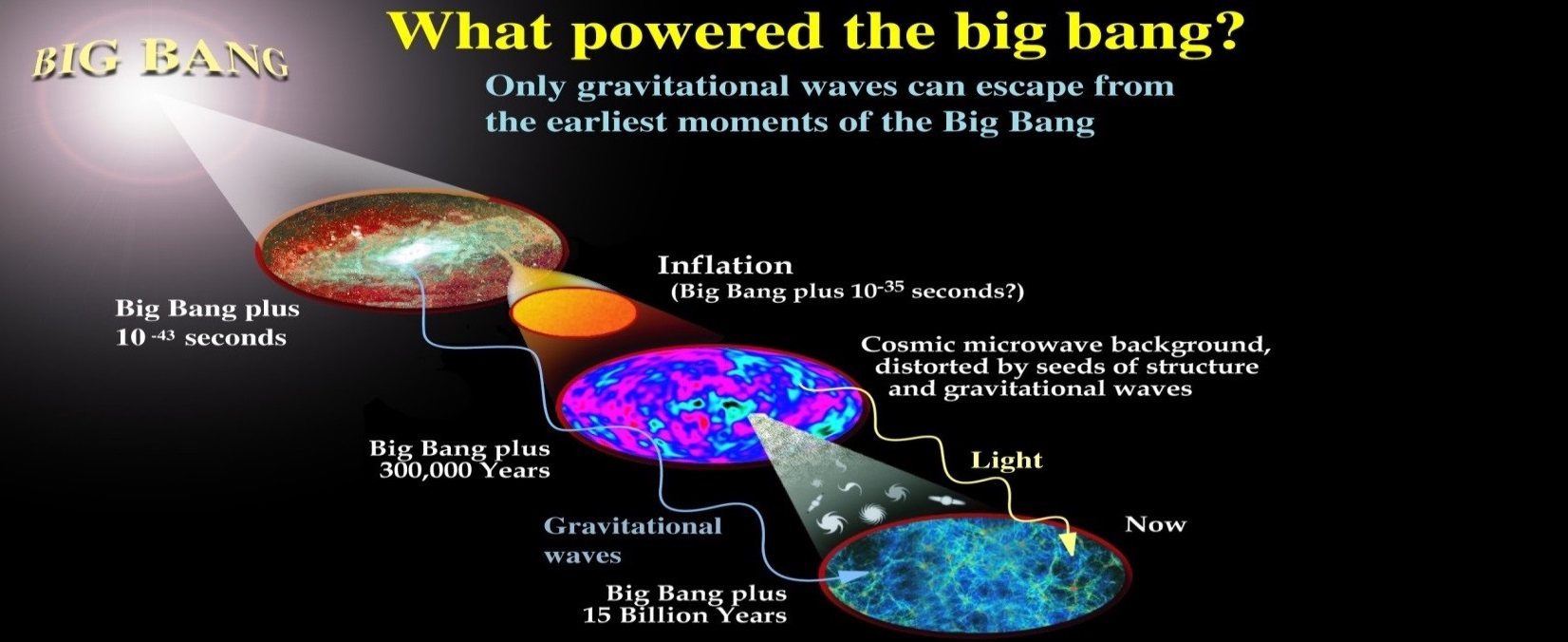

Big Bang image from the Open University, see physics and astronomy – The Big Bang

Big Bang image from the Open University, see physics and astronomy – The Big Bang

Oddly enough, not much happened for a while, even though Einstein gave his endorsement. He attended Lemaître‘s presentation in Pasadena in 1933 and said it was “the most beautiful and satisfactory explanation of the creation that I have ever heard”. Perhaps the hiatus was because Lemaître was a priest. Perhaps his exploding cosmic egg sounded too much like Genesis. Perhaps it suffered from a Chicken and Egg problem. Where did this cosmic egg come from?

Gamow takes up the baton

It wasn’t until 1946 and George Gamow that things moved on. Gamow had been a student of Friedmann’s. He wrote a one-page paper on the Expanding Universe and the Origin of Elements. He said abundance should decrease with atomic weight, but that this doesn’t happen in the second half of the periodic table. He also said the expansion must have been fast enough to reduce the initial high density by an order of magnitude in about a second, and that the conditions necessary for nuclear reactions existed for a very short time – less than the beta-decay period of free neutrons. He said “We can anticipate that neutrons forming this comparatively cold cloud were gradually coagulating into larger and larger neutral complexes which later turned into various atomic species by subsequent processes of β-emission”. He finished by saying the high abundance of hydrogen must have resulted from the competition between neutron decay and the “coagulation process through which these neutrons were being incorporated into heavier nuclear units”.

Alpher Bethe Gamow

Gamow wrote another one-page paper in 1948 with Ralph Alpher and Hans Bethe. It was called The Origin of Chemical Elements. They said the elements must have originated “as a consequence of a continuous building-up process arrested by a rapid expansion and cooling of the primordial matter”. They talked of compressed neutron gas decaying into protons and electrons with capture of the remaining neutrons by protons to form deuterium nuclei, then subsequent neutron captures resulting in heavier and heavier nuclei. They said the observed slope of the abundance curve must be related to the time period permitted by the expansion process rather than the temperature of the neutron gas. And that individual abundances must depend not so much on their intrinsic stabilities as on the values of their neutron-capture cross-sections. They gave an equation governing the process along with a relative abundance chart, and said the process must have been completed when the temperature of the neutron gas was still high, otherwise the observed abundances would have been strongly affected by slow neutrons. This was the famous Alpher Bethe Gamow paper, and it was wrong. That’s because of the mass-5 roadblock. No element has a stable isotope with an atomic mass of five, so the continuous buildup idea just didn’t work. Furthermore it starts with a neutron gas. Where did this neutron gas come from?

Alpher Herman Gamow

Philip “Jim” Peebles gives a wealth of detail in his 2013 paper Discovery of the Hot Big Bang: What happened in 1948. He says the Alpher Bethe Gamow paper assumes cold Big Bang cosmology and makes no mention of thermal radiation. But he also tells us of no less than ten papers in 1948 by Alpher, Bethe, Gamow, and Robert Herman:

Image from Jim Peebles’ Discovery of the Hot Big Bang: What happened in 1948

Image from Jim Peebles’ Discovery of the Hot Big Bang: What happened in 1948

They include Evolution of the Universe where Alpher and Herman said “the temperature in the universe at the present time is found to be 5°K”. This is taken to be the first prediction of the cosmic microwave background radiation or CMBR, which has been measured at 2.725°K. Peebles however says there are issues: “Their numerical value is not significant because it depends on the present baryon density, which was very uncertain, and they compute element buildup along the wrong path”. He also quotes Fred Hoyle saying “the age of the universe in this model is appreciably less than the agreed age of the Galaxy. Moreover it would lead to a temperature of the radiation at present maintained throughout the whole of space much greater than McKellar’s”.

The temperature of space

For more information see the Jodrell Bank introduction to cosmology article where you can read about the temperature of space. It starts with Charles Fabry in 1917: “For interstellar space in our Galaxy he calculated this to be 3° absolute, or 3 K in modern notation”. You can also read about a temperature with a very restricted meaning and about Andrew McKellar. He wrote a paper in 1940 on the Evidence for the Molecular Origin of Some Hitherto Unidentified Interstellar Lines. On page 6 he talked about spectral lines R(0) and R(1) and said “if R(1) is not more than one-third, one fifth, or one-twentieth as intense as R(0), the maximum ‘effective’ temperature of interstellar space would be 2.7° K, 2.1° K, and 0.8° K, respectively”. The Jodrell Bank article also talks about ylem and after. It says as Gamow’s team studied the big bang they realised that the ylem could not have been pure neutrons, and in fact mostly consisted of gamma-ray photons. It also says they “never proposed an experimental search for these photons. One reason was that Gamow had heard about Eddington’s ‘temperature of space’ and thought that this would be difficult to disentangle from the relic photons from primordial nucleosynthesis”. The article also says that Gamow, like McKellar, “failed to spot the enormous difference between starlight with energy density equivalent to a 3 K blackbody, and a genuine blackbody spectrum”. And that “Alpher and Hermann had privately consulted radio astronomers and experimental physicists, and were told that the measurement was impossible”. The article goes on to say the general attitude of astronomers and physicists at the time was that a highly speculative theory of “creation” had failed.

Fred Hoyle and the steady state

That was perhaps in part due to the competition from Fred Hoyle and others. Hoyle was into stellar nucleosynthesis, and wrote a paper in 1946 on The Synthesis of the Elements from Hydrogen. He was deeply involved in the field and a co-author of the famous B²FH paper. The bottom line is that stellar nucleosynthesis trumped Big Bang nucleosynthesis because the latter more or less stops with helium. That’s perhaps why Hoyle was so critical of the Big Bang. And perhaps why in 1948 he came up with a steady state theory. The irony of course is that in 1949 he used the phrase “Big Bang” in a disparaging fashion on BBC radio, and the name stuck. He was happy enough with the expanding universe, but he didn’t like the idea that the universe had a beginning. I can empathize with that. He was also skeptical of the way the CMBR was presented as proof of the Big Bang. He said it could have been caused by something else. I have some sympathy for that too, because as they say, you can’t prove a theory right, you can only prove it wrong. All the more so because in 1940 McKellar had said the maximum effective temperature of interstellar space would be 2.7° K. However I have no sympathy for Hoyle’s “creation field” where matter pops into existence spontaneously, like worms from mud. Or for Bondi and Gold’s “perfect cosmological principle”. Because as per Sandra Faber’s counterbalance article about the steady state universe, quasars and radio galaxies are more frequent at large distances and so earlier times. So we have good evidence that the universe has changed, and thus is not a steady-state universe.

Discovery of the CMBR

That’s perhaps why the discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation is generally accepted as good evidence for Big Bang cosmology. Alan Guth gives an account in his 1997 book The Inflationary Universe. On page 58 he tells us how Arno Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson were refurbishing Bell Labs’ 20-foot Holmdel Horn antenna at Crawford Hill in New Jersey for use in astronomy. They converted it into a Dicke radiometer using a “cold load” dewar of liquid helium at 4.2° K. By switching the receiver from the cold load to the antenna they could determine the true signal from the antenna. They ran a test tuned to a wavelength of 7.35cm, expecting their background subtraction to leave a zero signal. However the system “seemed to be picking up some unforeseen source of microwave signal”. It was the same in all directions and it didn’t vary with the time of day or season. Guth tells how 30 miles away in Princeton a group of physicists spearheaded by Robert Dicke himself had regular Friday-night discussions followed by beer and pizza. Dicke favoured a cyclical cosmology, whereby at the time of the bounce the universe must have been so hot that atomic nuclei were shattered into protons and neutrons. Hence “there must be a radiation background – an afterglow of this intense heat – that would continue to permeate the universe”.

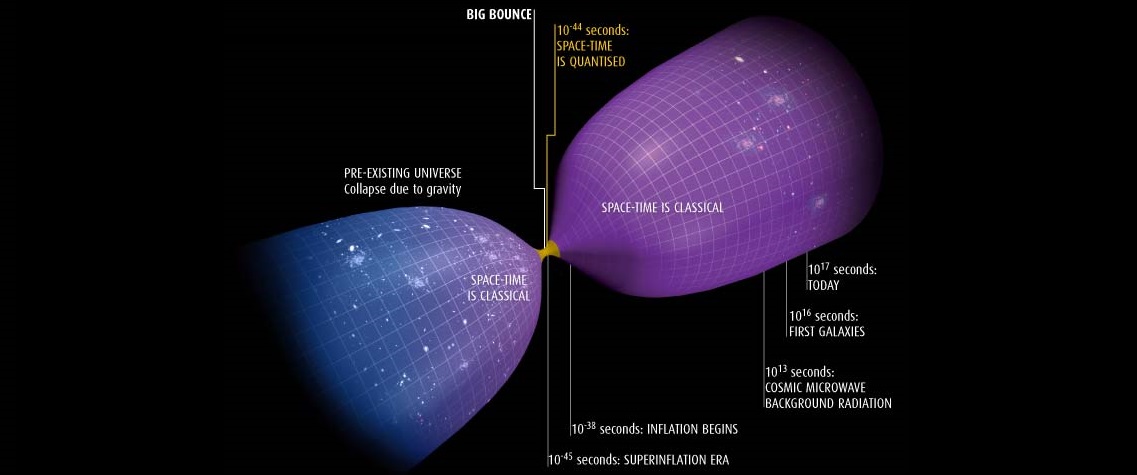

Big bounce image from New Scientist article From big bang to a big bounce by Anil Ananthaswamy. also see Baez

Big bounce image from New Scientist article From big bang to a big bounce by Anil Ananthaswamy. also see Baez

Dicke got two young researchers Peter Roll and David Wilkinson to look for the background radiation using a 1ft horn antenna on the roof, and asked Jim Peebles to “think about the theoretical consequences”. The result was a 1965 paper Cosmology, Cosmic Blackbody Radiation and the Cosmic Helium Abundance which predicted a blackbody spectrum. Unfortunately Peebles couldn’t get it published because of an issue with credit given to prior work. However he gave a talk in Baltimore, and in the audience was his old friend Kenneth Turner. Turner later mentioned it to a fellow radio astronomer Bernard Burke, who told his friend Arno Penzias. Then “Dicke received a phone call from Penzias, and the Princeton crew was soon on the road to Crawford Hill. When Dicke and his collaborators saw the results Penzias and Wilson were obtaining, they were quickly convinced that the Bell Labs team had made the crucial discovery”. The two groups decided to submit back-to-back papers to the Astrophysical Journal. The papers appeared in July 1965. They were A Measurement of Excess Antenna Temperature at 4080 Mc/s by Penzias and Wilson, and Cosmic Black-Body Radiation by Dicke, Peebles, Roll, and Wilkinson. Guth says “the echo of the Big Bang had been found”.

Missed opportunities

It might have been found previously. In the 1965 NASA cosmic hiss article you can read how Andrei Doroshkevic and Igor Novikov published a Big Bang study saying the remaining heat would now be between 1 and 10 degrees Kelvin. They even proposed the use of the Holmdel horn measurements made in 1961 by Edward Ohm, who “had already identified in his data what seemed to be a 3.3 degrees Kelvin background radiation”. There are conflicting reports about that, but such is life. The article also says “Ten years ago Émile Le Roux reported a microwave background radiation of 3 degrees Kelvin, plus or minus 2 degrees at the Nançay Radio Observatory”. And that “In 1957 it was Tigran Shmaonov who nearly made the discovery. He reported measuring background temperature of 4 degrees Kelvin, give or take 3 degrees”. Ned Wright says that the claims that Le Roux measured the CMB in the 1950’s are incorrect. Whatever the truth of it all, something that is true is that the paper by Dicke et al talked about an oscillating universe. So according to them the evidence for the Big Bounce had been found. However they covered the bases by saying that even if the universe had a singular origin it might have been extremely hot in the early stages. But they didn’t say much about previous work by Gamow and his collaborators.

Bitterness

In a 1984 oral history interview with Martin Hewitt, Peebles wondered if the referee who rejected his 1965 paper was Gamow himself, but Hewitt said it wasn’t. Hewitt had previously interviewed Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman who said they reviewed Peebles’ paper and were appalled “because there was absolutely no indication that he had read any of our early work”. They were still unhappy with the references to their work in 1965 paper by Dicke et al. Alpher said “he did refer to the fact that you, Gamow and I had discussed an early hot, dense universe, but that was about it. There was no reference at all to any of the other stuff that we had published”. The interview makes it clear that they were bitter. The irony is that in Jean-Pierre Luminet’s rise of big bang models (5): from Gamow to today you can read that whilst Penzias and Wilson were awarded a Nobel prize in 1978, “at the moment of their discovery, they believed instead in the theory of continuous creation”. See PBS for a mention of that. Or the 2005 John Oakes interview with Penzias and Wilson where they say “along came this wacky idea from Princeton. They were actually thinking about multiple big bangs”. That’s where Wilson said cleaning up after the birds “did knock a little bit off our measured temperature. There was some radiation from the bird droppings”. Genesis and Hebrew revelations were also mentioned. For some more irony see Penzias’ Nobel lecture, where he said “Hoyle concluded that about ninety percent of the helium found in stars must have been made before the birth of the galaxy”. And that “attention was turned to helium formation in the early stages of an expanding universe, reviving work begun by George Gamow some sixteen years earlier”. Because of Hoyle’s helium problem, the Big Bang was born again.

The Big Bang was born again

The Big Bang was born yet again with COBE in 1992, which measured the CMBR black-body curve and the anisotropy that was said to be essential for structure formation. It was accompanied by a great deal of media coverage including pronouncements such as “the discovery of the century” and “seeing the face of God”. It led to Nobel prizes in 2006, to WMAP operating up to 2010, and to Planck operating up to 2013. Nowadays there’s plenty of articles about the Big Bang. Such as The Big Bang article on the NASA astrophysics website. Or the DAMTP Hot Big Bang article. Or the Scholarpedia modern cosmology article by George Ellis and Jean-Philippe Uzan. However the various articles sometimes cause confusion. The NASA article says one problem that arose from the original COBE results and persisted with WMAP was that the universe was too homogeneous. That comes as a surprise. The DAMTP article says “about ten billion years ago, the Universe began in a gigantic explosion”. Ten billion years ago? That doesn’t sound right. The Scholarpedia article has Hot Big Bang down as the third epoch, after Start and Inflation. That doesn’t sound right either, because in most articles the Big Bang is the thing that came first, before inflation:

Image by NASA, see NASA’s space place

Image by NASA, see NASA’s space place

There’s arguably more confusion in the NASA WMAP foundations of Big Bang cosmology article. It says “it is beyond the realm of the Big Bang Model to say what gave rise to the Big Bang”. But surely that’s what the Big Bang is all about? It’s the $64,000 dollar question. How did the universe begin? Or not, as the case may be. I think it’s the biggest mystery of them all. Particularly because of the supernovae observations that provided evidence of the accelerating expansion of the universe. If the expansion is speeding up, was it slower in the past? And was there a time when it was very slow?

God did it

See for example The 5 Biggest Questions About the Universe written by Dan Falk for NBC News. He asks questions such as What is Dark Matter? along with What is Dark Energy? and What’s Inside a Black Hole? I think we can get somewhere with such questions, in that when you read enough you can come up with some answers that make sense. Falk also asks What Came Before the Big Bang? and I think you can get somewhere with that too. Not however by saying things like God did it, which is a turtles-all-the-way-down non-answer pretending to be an answer. I say that because the word universe is derived from “uni” as in unicycle, and “verse” as in vice versa. It means turned into one. It means everything. Not just that part of everything that was created by some other part of everything. Hence God did it just doesn’t cut it.

A quantum fluctuation did it

Nor did Stephen Hawking’s 2010 book The Grand Design co-authored with Leonard Mlodinow. It caused a rumpus. See Hamish Johnston’s Physicsworld blog for M-theory, religion and science funding on the BBC. The crux of it is that Hawking said a quantum fluctuation did it, and it was still a turtles-all-the-way-down non-answer pretending to be an answer. But somehow it was worse, because it didn’t come from a bishop in a palace thumping his bible. It came from a scientist in a wheelchair plugging his popscience book. All the more so because in his 1974 Hawking radiation paper, Hawking talked of negative frequency waves propagating backwards to past null infinity. All the more so because he’d previously said the universe can be likened to a black hole in reverse, but he didn’t talk about the infinite gravitational time dilation and the zero “coordinate” speed of light at the event horizon. He didn’t talk about the very reason the black hole is black. Or about the upshot: moving away from a black hole across space can be likened to being in a universe expanding over time. Then when you play it backwards, as you move towards the black hole, you suffer ever-increasing gravitational time dilation, in line with the reducing speed of light. GRBs and firewalls apart, you end up with the frozen-star black hole, wherein it takes an infinite time to cross the event horizon, so you never ever do. And yet people say you do. They say you do a hop skippity jump over the end of time, and then you meet the point singularity in finite proper time. All this reminds me of a picture I saw. A picture where, if the black hole parallel is correct, something is missing:

Expansion of the universe image by NASA/WMAP, see Foundations of Big Bang Cosmology

Expansion of the universe image by NASA/WMAP, see Foundations of Big Bang Cosmology

What’s missing is the curve that gets flatter as it approaches the origin. The curve that describes a universe where the expansion was slower in the past. Like the M2 curve on page 9 of Ari Belenkiy’s 2013 paper about Friedmann. Or the static coasting universe in Jim Brau’s astronomy 123 course:

Image by Jim Brau, see The Big Bang and the Fate of the Universe

Image by Jim Brau, see The Big Bang and the Fate of the Universe

The image also shows a curve labelled “No Big Bang” which is associated with the big bounce. I don’t favour the big bounce because I can’t conceive of any way by which space might contract. Space is like some gin-clear ghostly elastic solid. It has its stress-energy, stress is directional pressure, and a stress ball expands when you open your fist. It doesn’t contract, no matter what the energy density. Because a gravitational field is a place where space is neither homogeneous nor isotropic. On the largest scale the universe is both, and always was. Because there once was a time when the speed of light was zero everywhere, and light can’t go slower than that. Nowadays the speed of light is not zero, and space expands. Not because of some kind of gravitational repulsion. But because at some fundamental level, space and energy are the same thing, like some kind of compressed gin-clear ghostly elastic solid. This doesn’t feature in the particle-physics Big Bang papers, nor does general relativistic time dilation, where the speed of light and the speed of all other processes depends on energy density. Yes Joao Magueijo and Andreas Albrecht came up with their VSL theory in 1998, but that gets it back to front. The speed of light in the early universe must have been slower, not faster.

The dawn of time

Come with me to the dawn of time. Outside our bubble of artistic licence the energy density is high. So very high that the outside environment is subject to infinite GR time dilation. It’s like the whole universe is like the frozen-star black hole. Note the word frozen. People tend to say the early universe was hot, but heat is an emergent property of motion. And in a frozen universe, there isn’t any motion. There is no heat. There is no radiation either, not when the speed of light is zero. This early universe where everything is frozen is a strange place. Motion is king, and if there is no motion there is no light. And if there is no light there are no photons, and no electrons too, because we make electrons out of photons in pair production. The same applies to protons and other particles, so there is no matter in the usual sense. Not only that, but clocks “clock up” regular cyclic motion, so without motion, there is no time. It’s hard to say what does exist. You can say energy exists, because that’s the one thing we can neither create nor destroy. But if nothing moves you can’t measure any distance, so does space exist? Maybe it’s space Jim, but not as we know it. It reminds me of the gravastar, where the central region is “a void in the fabric of space and time”. It’s like the early universe was like a black hole and nothing else. Like it was frozen space and a hole in space, with no space around it. Entropy is “sameness”, and everything is the same, so entropy is high. There’s no room for difference until the raum gets bigger. There’s no overall gravity either, because on the largest scale the energy density is homogeneous. And of course gravity doesn’t make space fall down. We do not live in some Chicken Little world. So the universe was never going to collapse.

Why is there something rather than nothing?

Yes, perhaps there was a phase change, like the way a block of C4 changes into a gas at 8000 feet per second. But as to why there was something that changed, I don’t know. I don’t know why there is something rather than nothing. I don’t know how the universe can be created from nothing. Ex-nihilo. Spontaneously, like worms from mud. But I suppose I know something happened to release the pressure, because here we are. Some say a quantum fluctuation did it, some say quantum tunnelling did it, and some say a phase change did it. I don’t know if any of them did it. But I can imagine an early universe expanding at some slow creeping pace. Like a pumpkin grows. If you were in that universe, you might be subject to what looked like infinite time dilation. So if you could make a claim, you might claim that this slow creeping pace was an infinite pace. After a while you might be subject to a huge but non-infinite time dilation. Then you might claim that the slow creeping pace was extremely rapid. And whatever you claim, later observers might claim the same, because they have no external yardstick. Then they might claim that the universe was created in finite proper time. Just as they might claim that it takes finite proper time to fall through the event horizon. When you never ever do. See the 1989 paper Did the big bang begin? by Jean-Marc Lévy-Leblond. Helge Kragh says the idea of two time scales was first discussed by Edward Arthur Milne, who distinguished between what he called kinematic and dynamic time.

It isn’t so cut and dried as people say

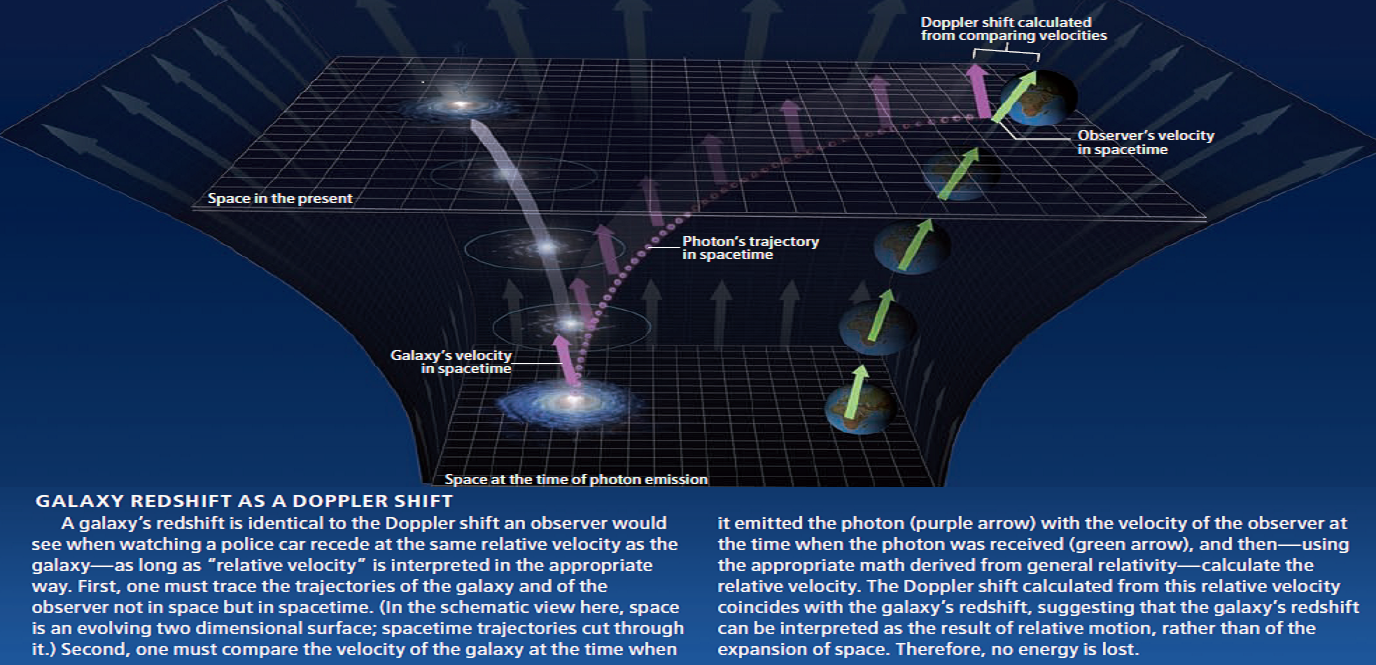

On page 10 of his 2013 paper Jim Peebles said singularity theorems “now convincingly argue against a bounce under standard general relativity theory”. I concur that we can argue against a bounce using standard general relativity. That’s because even if there was no measured redshift, I’d be saying the compressed gin-clear ghostly elastic solid just has to expand. But I do not buy singularity theorems, because I know light can’t go slower than stopped. So as for what banged? I’m not sure anything did. And as for how did the Universe begin? I’m not sure it ever did. So when it comes to the hot Big Bang theory, I’m not sure it’s as cut and dried as people say. Not when there’s stars that appear to be older than the universe. Not when there’s a lithium problem. Not when the doppler-shifted photon doesn’t lose any energy. Or the ascending photon. Or the CMBR photon:

Image by Tamara Davis and Scientific American, see Is the Universe leaking energy?

Image by Tamara Davis and Scientific American, see Is the Universe leaking energy?

That’s because energy is conserved, because gravitational field energy is not negative, and because the universe is not some free lunch. But since I’m happy enough that it’s getting bigger and that old galaxies are different, I’m happy enough with the Big Bang. Even if it isn’t all cut and dried. Even if it didn’t bang, and was more of a whimper. All in all I’d say it’s the Big Bang Jim, but not as we know it.

How anyone can swallow the velocity-distance relation is beyond me. It places us at the center of the universe. That’s enough to dispose of the Big Bang.

Laurence, think about the raisin cake analogy, and imagine you’re a raisin. Let’s not worry about being near the edge just now. As the cake expands, all the other raisins around you are moving away from you. Raisins a long way off are moving away from you more than those near by. You don’t have to be at the centre of the cake to see a velocity-distance relation.

Universal expansion itself is conceptually impossible in the three real dimensions of our nontheoretical world. But its fundamental viability is rarely questioned, if at all, despite all of its obvious incongruities.

How can the universe remain uniform, homogeneous and isotropic as we observe, if it’s expanding? It’d have to be diffusing exponentially. The inverse square law, a basic principle of (three-dimensional) spherical geometry, would cause its density to decrease inversely as the square of the distance from its origin. Given its presumed finiteness, how could it not? (Intensity at the surface of a sphere, which is the same as density, is proportional to one divided by the square of its radius.)

That diffusion, if it existed, would be easily discernible through the exponential dispersion of galaxies and their redshifts. Their dispersion would also reveal an origin’s location, if one exists. Even if inflation were true and somehow created a visible horizon, their dispersal would still be perceivable and still indicate the origin’s direction. If there’s no diffusion, the universe cannot be expanding. And if it’s not expanding, the big bang can’t be real.

Even if it was somehow able to remain uniform, which isn’t physically possible in three dimensions (see a tetrahedron, octahedron, and icosahedron, platonic shapes where the vertices of their equilateral triangles scribe a sphere with a radius that’s always less than the distance between them), but let’s say it was, its finiteness would still be confirmed by a telltale pattern of galaxies that appeared to condense across the sky. (That assumes we didn’t end up by chance at its exact center.) Try visualizing what that would look like.

Imagine that we were located halfway between the universe’s center and its perimeter. Galaxies would have to be arrayed two-dimensionally, condensing visually, not physically, over the entire sky into a single cluster that culminated in the direction of its center. From our vantage point, it’d be less dense in the direction where the perimeter is closest, one-quarter the total distance of its diameter, and more dense in the direction of its center, three-quarters its total diameter. Despite its uniformity, we’d still see a difference in the number of galaxies that proportionally was more than three to one.

The pattern would be essentially the same for a diffusing universe. It’d just be more exaggerated with fewer galaxies in the direction where the perimeter was closest where they’d be more dispersed and more galaxies in the direction of the center where they’d be more condensed.

Its expansion would also be confirmed by cosmological redshifts that correlated with the pattern. They’d have to be progressively increasing in magnitude, peaking directly opposite our galaxy’s outward-bound direction of travel. That’s the direction where their distance would be the farthest and their recessional velocity/space’s stretching would be the greatest. This would have to hold for a diffusing universe as well.

This distinct pattern would also clearly indicate the location of the universe’s origin. And the pattern’s existence would also decisively confirm the big bang. But the opposite would have to be true. If it doesn’t exist then the universe cannot be finite. Nor can it be expanding. And again, the big bang, even if it were uniform, can’t be real.

Ken: I don’t think the universe is homogeneous and isotropic. We observe gravitational anomalies which are attributed to dark matter, but I think they are clear evidence of inhomogeneous space. I do however think the universe is expanding. That’s because I think of space is being akin to some kind of ghostly gin-clear compressed elastic. So it expands rather like a stress ball expands when you open your fist. That stress ball is finite, and I think the universe is finite too. If it wasn’t, it couldn’t expand. Having said that, I don’t think the Big Bang banged. I think inflation is junk, I do not believe in point singularities, and there must have been something akin to gravitational time dilation in the early universe.

.

As regards our location in the universe and the galaxies, I think in terms of being in the middle of a forest. You see trees all around, and everything looks the same in all directions. But you do not then declare that the forest goes on forever, and consists of the same trees forever, with no centre. It would be the same if you replaced the trees and the forest with raisins in a cake. Our galaxy doesn’t really have an outward-bound direction of travel, and nor does a raisin in the cake.

.

I hope you enjoy some of the other articles I’ve written about cosmology. I think the correct understanding of general relativity tells us that much of the Standard Model of cosmology is obviously wrong, but not everything. Unfortunately it would seem that many cosmologists like to peddle myth and mystery rather than study the underlying physics that would allow them to distinguish between hokum and the real deal.

I think what you have done here is a great description of what we actually know and what we don’t know. We have no idea of the size of the universe, and no idea of where the center is. Now how the hell would we ever figure out where the center is? That should be a major research topic with many centers of research looking for answers to that question.

The reason no one is looking for the universe’s center is that most cosmologists don’t believe it has one. Or sometimes they’ll characterize the center as being everywhere. Their belief is based on Einstein’s “finite and yet unbounded” universe that they’ve credulously adopted as reality.

In his 1961 book, Relativity: The Special and the General Theory, Einstein whimsically imagines a curving non-Euclidean (a geometry that’s not straight, square, or parallel) universe that expresses two-dimensionally like the surface of a sphere. Its spherical two-dimensionality would theoretically explain away a finite universe’s tendency to condense exponentially from gravity. (It’d do the same for its exponential diffusion from expansion.)

He “reasons” that if the universe expressed two-dimensionally as the curving surface of a sphere, gravity’s effect would become uniform and could then be countered by employing a “cosmological term,” a constant that would (mathematically) prevent it from collapsing in on itself while maintaining its observed uniformity. He later abandoned his cosmological constant (that we’ve all heard he regarded as his biggest mistake) in favor of Alexander Friedmann’s (a Russian mathematician 1888-1925) idea of expanding space that he thought to be a more natural solution.

Despite the overt unworkability of its two-dimensionality, this is in essence general relativity’s standard model big bang that’s embraced as orthodoxy. The analogy that’s often presented is a balloon covered uniformly with dots that represent galaxies. As it inflates, the dots move equally away from one another.

Space’s counteracting expansion conceptually works in two dimensions. But it could never counteract gravity’s exponential condensing in three dimensions. To produce a uniform result in three dimensions, the universe’s expansion would be required to somehow decrease exponentially from its center out. That’s physically impossible. But so is its two-dimensionality. There’s no existence in two dimensions. Two dimensions can only define a location that’s planar.

Einstein justifies his two-dimensional, finite yet unbounded illusion by adopting “the three-dimensional spherical space which was discovered by [Bernhard] Riemann” (a German mathematician 1826-1866) that melds our three-dimensionality with a two-dimensional space that manifests as a sphere’s surface. He asserts that in his universe, someone can “draw lines or stretch strings in all directions [meaning spherically, three-dimensionally] from a single point… At first, the straight lines which radiate from the starting point diverge farther and farther from one another, but later they approach each other, and finally they run together again at a ‘counter-point’ to the starting point. Under such conditions they have traversed the whole spherical space.”

This is a physically impossible scenario. It’s also inherently conflicted. The strings are first diverging three-dimensionally, which can only continue indefinitely. But then he has them somehow magically start to converge two-dimensionally.

Despite the obviousity of its absurdities, we still affirm his delusive narrative by agreeing that someone with a powerful enough telescope could look out in any direction, three-dimensionally, and see the backside of our own galaxy, which is just as impossible and conflicted. But at the same time, we also hold that someone with a powerful enough telescope could look out, again in any direction three-dimensionally, and see back in time almost to the universe’s inception. Neither are conceptually possible, and they conflict with one another.

Einstein asserts that visualizing his two-dimensional three-dimensional “…space means nothing else than that we imagine an epitome of our ‘space’ experience, i.e. of experience that we can have in the movement of ‘rigid’ bodies. In this sense we can imagine a spherical space.” None of this has a rational interpretation. It’s complete nonsense.

General relativity certainly looks sophisticated and it sounds legitimate. But when all of its high-sounding technical rhetoric is filtered out and all of its illusive mathematical gimmickry is stripped away, we’re ultimately still left existing in two dimensions. Any way you cut it, that doesn’t work.

Any rational (unindoctrinated) individual of average intelligence with minimal visualization skills easily perceives that if the universe were actually finite it’d have to have a center, and gravity would cause its condensing. And if it were expanding, the simple geometry of a sphere would cause it to be diffusing.

The bottom line is, if the universe can’t be two-dimensional and is not condensing or diffusing, it cannot be finite. Nor can it be expanding. So the big bang cannot be real. Cosmological redshift has to be indicative of something other than space’s stretching and cosmic microwave background radiation has to originate from a source other than the big bang’s primordial conditions.

Ken: I agree with a lot of what you’re saying. Yes, modern cosmologists follow an orthodoxy. But it isn’t Einstein’s orthodoxy. Yes, in 1917 Einstein struggled with his boundary conditions, and came up with the “outlandish” idea of a closed curved universe instead. Yes, on a postcard to Willem de Sitter he said “I am curious to see what you will say about the rather outlandish conception I have now set my sights on”. Yes in 1921 he talked about placing disks on a sphere and how two-dimensional creatures might discover they live in non-Euclidean space. He also said “from the latest results of the theory of relativity it is probable that our three-dimensional space is also approximately spherical”. But in 1932 he and de Sitter dropped the idea in favour of flat space in their Einstein-de Sitter universe. Modern cosmologists have somehow missed that.

.

As for his 1961 book, the guy died in 1955! But I take your point about gravity. For some strange reason Einstein missed the bleedin’ obvious. A gravitational field is a place where space is ”neither homogeneous nor isotropic”. And if the universe is homogeneous and isotropic on the largest scale, then there is no overall gravity. It’s as if he had a breakdown or a stroke or a crise or something, and totally lost his mojo in the thirties.

.

See https://physicsdetective.com/the-edge-of-the-universe/ for something about Friedmann. The guy didn’t know what he was talking about. Gravity has got nothing to do with spatial curvature. IMHO once you understand gravity you see the mistakes in the Standard Model of cosmology, and the way its advocates appeal to Einstein’s authority. But IMHO that doesn’t mean you then dismiss the idea of the expanding universe. As for why Einstein didn’t predict it, I just don’t know. It comes back to him losing his mojo at some point. I wish I had more time to look into it. I have been run off my feet lately, but I will have more free time going forward

.

PS: Apologies, the comments got disabled by an after n days setting change that crept in on an upgrade. I fixed it.

Thanks Doug. As to figuring our where the centre of the universe is, I’m not sure we can. Maybe we can do deep field observations in different directions. But maybe we are like the man in the woods. All he can see is trees. He has no way to find out where the woods end in any direction.

.

As for this being a major research topic, I am not optimistic. The academics can’t even tell you what a photon is. Or an electron. Or how gravity works. The universe is a lot trickier than things like that.

.

Apologies, some upgrade had turned on a setting that disabled comments on posts over then 14 days.

Hi John,

Recently I’ve been looking at some of Unziker’s YouTube videos, and other sources. Have you ever heard about the steady state model of the universe by Jayant Narlikar? It assumes basically that it’s mass that’s varying over time, so there’s no expansion of the universe, and the galactic redshift is the result of the decrease in wavelength due to the electron’s increase in mass. It postulates that the mechanism for the increase is that when a particle is created, it starts interacting with nearby matter in a spherical volume expanding at the speed of light, so the mass inevitably increases over time. This is extremely similar to what unziker talks about in his “big numbers” videos and mach’s principle, where the inertia of bodies depend from all other bodies in the universe. I suggest watching the brief video of See the Pattern called “Variable Mass Theory: Intrinsic Red-Shift”, where this is explained in detail.

If we add the hypothesis that the electron is really a photon trapped in some configuration, and that the speed of light is variable where there’s matter around, we can see a very convincing pattern emerging. The “density” of space depends on how much energy that space has, and with increasing time the amount of energy in a volume is destined to increase as radiation from a bigger sphere is included.

I’m not sure if I’ve heard of the steady state model of the universe by Jayant Narlikar. I had a quick look (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayant_Narlikar) and note that it’s based on Mach’s principle. I am not a fan of Mach’s principle, so I may have encountered Narlikar’s model and dismissed it. The mass of a body is a measure of its energy-content works for me. Because of the wave nature of matter. And because photon momentum is a measure of resistance to change-in-motion for a wave moving in a linear path, whilst electron mass is a measure of resistance to change-in-motion for a wave moving in a closed path. It’s like the electron is a photon in a box of its own making. See https://arxiv.org/abs/1508.06478.

.

I don’t like the assumption that mass is varying over time because that’s creation of energy ex nihilo. Also, I don’t like “the galactic redshift is the result of the decrease in wavelength due to the electron’s increase in mass” because I don’t think that wavelength decreases at all. The ascending photon does not change wavelength, and I think the same is true of CMBR photons. See the article I mentioned above, Is the Universe leaking energy? I think the answer is no.

.

I will have a look at Unziker’s videos.

.

Re what you said here: If we add the hypothesis that the electron is really a photon trapped in some configuration, and that the speed of light is variable where there’s matter around, we can see a very convincing pattern emerging. The “density” of space depends on how much energy that space has, and with increasing time the amount of energy in a volume is destined to increase as radiation from a bigger sphere is included. I don’t agree with the conclusion I’m afraid. I think space and energy are the same thing, and that space is like some kind of gin-clear ghostly elastic. Compressed elastic. And finite. So space just has to expand. And as it does, the spatial energy density drops. So the speed of light increases. Which means Andreas Albrecht and João Magueijo got it back to front.

John,

Some observations and questions that pertain directly or indirectly to the beginning of the universe.

(1) Per General Relativity, time slows down, or proceeds at a slower pace, in a gravitational field than it does outside of, or at a distance from, the field. As you have indicated, and I ascribe to your narrative, the Big Bang took a lot longer than conventional physics imagines, as viewed or conceptualized from our point of view in this middle-age expanded cosmos. At the beginning, before the creation of matter particles, the energy density of space was so high that time must have proceeded at a snail’s pace relative to our present experience of accumulated motion. The first second, as described in contemporaneous cosmological accounts, likely endured untold eons of time pursuant to our current measures.

Question: Do you know whether the computations made by establishment physicists as to events in the first nanoseconds (10-43 range) of the Big Bang take General Relativity into account? It appears likely that no spatial density gradient existed in the very early universe, rather only a uniform and humongous density. Like the absence of a gradient or non-homogeneity within the event horizon of a black hole. I think you would concur with this and have perhaps already provided your views.

(2) You have written about pair production, of electrons and positrons. You have also proposed that protons be considered as antimatter, thereby eliminating the cosmology problem as to the purported imbalance between matter and antimatter. I would think that the essential accounting for physicists would concern energy, momentum, angular momentum, and charge, under conservation laws, and that matter versus antimatter is an inessential distinction.

Questions: Owing to the vast amount of atomic hydrogen (basically protons and electrons) in the universe, I surmise that the early universe, during one phase or another, must have witnessed a kind of elementary-particle production that produced roughly equal numbers of protons and electrons. From your exposition of electron-positron pair production, I must imagine a process involving the near collision of two photons of very different energies, a higher-frequency photon resulting in a proton and a longer-wavelength photon for the electron. Have you encountered any such process in your detective researches? Can you propose such a photonic reaction?

NS

Neil: Sorry to be slow replying. I;ve had a lot to do of late. In answer to your points:

.

(1) Per General Relativity, time slows down, or proceeds at a slower pace, in a gravitational field than it does outside of, or at a distance from, the field. As you have indicated, and I ascribe to your narrative, the Big Bang took a lot longer than conventional physics imagines, as viewed or conceptualized from our point of view in this middle-age expanded cosmos. At the beginning, before the creation of matter particles, the energy density of space was so high that time must have proceeded at a snail’s pace relative to our present experience of accumulated motion. The first second, as described in contemporaneous cosmological accounts, likely endured untold eons of time pursuant to our current measures.

.

I agree with all the above. I have no issue with the expanding universe, but I don’t like the idea of creation ex nihilo. I don’t like the idea of an infinite universe either, because I don’t see how an infinite universe can expand. As I’ve said else where, things like the electron is the easy stuff, the beginning of the universe isn’t.

.

Question: Do you know whether the computations made by establishment physicists as to events in the first nanoseconds (10-43 range) of the Big Bang take General Relativity into account?

.

I actually don’t know I’m afraid. I imagine they do, but I took a quick look at https://math.uchicago.edu/~may/REU2013/REUPapers/Older.pdf and noticed “nothing can travel faster than the speed of light through spacetime”. This is wrong because there is no motion through spacetime. Also, it doesn’t cater for the situation where the speed of light is zero. Einstein talked about this in his 1939 black hole paper, but contemporary general relativity is different to Einstein’s general relativity.

.

It appears likely that no spatial density gradient existed in the very early universe, rather only a uniform and humongous density. Like the absence of a gradient or non-homogeneity within the event horizon of a black hole. I think you would concur with this and have perhaps already provided your views.

.

Yes. Whilst I’m not a fan of Hawking, I think he was right to compare the early universe to a black hole in reverse.

.

(2) You have written about pair production, of electrons and positrons. You have also proposed that protons be considered as antimatter, thereby eliminating the cosmology problem as to the purported imbalance between matter and antimatter. I would think that the essential accounting for physicists would concern energy, momentum, angular momentum, and charge, under conservation laws, and that matter versus antimatter is an inessential distinction.

.

I wouldn’t agree with that, because matter and antimatter have a nasty habit of annihilating, if they can. If you somehow journeyed to the edge of the universe and met a mirror-man version of yourself,. you might want to think about that “inessential distinction” before shaking his hand. LOL!

.

Questions: Owing to the vast amount of atomic hydrogen (basically protons and electrons) in the universe, I surmise that the early universe, during one phase or another, must have witnessed a kind of elementary-particle production that produced roughly equal numbers of protons and electrons. From your exposition of electron-positron pair production, I must imagine a process involving the near collision of two photons of very different energies, a higher-frequency photon resulting in a proton and a longer-wavelength photon for the electron. Have you encountered any such process in your detective researches? Can you propose such a photonic reaction?

.

No, I’ve never encountered this. From my understanding of how pair production works, I don’t think it could happen. I say that because I see a photon as a region of curved space, and the relatively mild curvature associated with 511keV photon isn’t sufficient to divert a 938MeV photon into a closed path.

Neil, I’ve read all your comments. So much to talk about! But I’m currently writing my next article, and will have to get back to you later. Meanwhile, I don’t think pair production can create an electron and a proton, but I don’t actually know this. Also meanwhile, I think we are singing from thge same hymn sheet. For myself, I’m thinking it was written by William Kingdon Clifford. See his 1870 space theory of matter. Like Maxwell, he died before his time. Sigh.

Thanks much, John. I appreciate your attention. I look forward to your next article. We are indeed singing from the same hymn sheet. You are the only living interpreter of physics that I can agree with. Sean Carroll is a distant second. I read his book “The Big Picture” but you describe a more accurate, more realistic, more in-tune, big picture. I think I mentioned that your exposition of the fundamental particles illuminated (pun, pun) physical reality for me. I also sigh for those who knew, Maxwell and Kingdon Clifford. And we cannot forget Einstein , Schroedinger, Mie, et al,. Their light shows the way. N

Hmm, one thing I think needs a closer look is the statement that energy can exist without time. Energy is a property of causality, I’m not sure if it can exist if the speed of light is zero. I don’t know if you’ve ever read any of the work of Ernst Mach, but you really should, especially his 1871 “History and Root of the Principle of the Conservation of Energy”:

https://archive.org/details/historyandrootp03machgoog

It also includes (I believe) the earliest statement of his famous principle in the footnotes. It’s a pretty short book, so I highly recommend giving it a read, especially consdering Mach’s influence on Einstein.

E: Thanks for the input. I’ll have a read of Mach’s book. But I’m not sure I’m going to agree with it if it says energy is a property of causality and can’t exist if the speed of light is zero. Have a read of What energy is, and you’ll see that I think energy is the same thing as space. Also take a look at The nature of time and you’ll see that I think time is a cumulative measure of motion. A black hole is a place where the speed of light is zero, and it has a massive gravitational field, so I’m sure energy can exist if the speed of light is zero. I haven’t read anything previously by Mach, because I dislike his famous principle. I know Einstein looked up to Mach, but he didn’t use Mach’s principle in his E=mc² paper. See the mystery of mass is a myth for more about mass. I think it’s just resistance to change-in-motion for a wave in a closed path.

I think I see what you’re getting at fundamentally: in order for any description of a physical process to be meaningful to living beings, you ultimately have to situate it inside of an absolute, classical spacetime. There are absolutely zero physicists contemplating these questions that are not alive. So the common interpretation of relativity was taken way to far, by trying to revolutionize human perception of the basic possibilities of reality entirely, instead of taking it as something contextual or emergent. Thus classical spacetime has to be viewed as a sacred vessel that contains all other phenomena, which we can call in their entirety the Einsteinian ether.

The concept of energy is meaningless absent it’s conservation. Conservation of energy is directly a consequence of causality. If speed of light is zero, then you have to assume some other way for processes to unfold, otherwise there is no causality. It’s existence is ultimately just something that you have to assume.

As for Mach’s principle, I honestly think the idea of an Einsteinian ether as a solid object encapsulates it perfectly. All it’s saying is that the mass-energy distribution of the universe is the origin of the universal rotational reference frame. And the mass-energy distribution is ultimately the same as the Einstein tensor. Einstein tensor = 8π * Energy-Momentum tensor

E: I am reminded of Minkowski “thundering” that space and time were defunct, and how Einstein said since the mathematicians have got hold of the relativity theory I hardly understand it myself. Or words to that effect. The moot point is that Einstein said space was the ether of general relativity. Not spacetime. It’s an important difference, because spacetime models space at all times, and hence is a static abstract arena. You do not travel along your worldline, because there is no motion in spacetime. This is why closed timelike curves do not permit time travel. Along with the fact that we live in a world of space and motion, wherein a cumulative measure of motion is the thing we call time. So classical spacetime is not a sacred vessel, and is not the Einsteinian ether. Whilst we doubtless agree on conservation of energy, we will have to agree to differ on the concept of energy itself. I view energy as the fundamental thing, and in essence the only thing. The same thing as space. Light is made of it, matter is made of it, and so are we. IMHO causality is not a thing that exists, it’s an abstract effect caused by the things that do exist. If the speed of light is zero, processes don’t unfold. Nothing happens. This is why I think there’s an issue with LIGO. And with Big Bang cosmology. See this article.

.

I’m happy with the idea of an Einsteinian ether as a solid object. A strange solid object, like some kind of gin-clear ghostly elastic. But what’s not so strange is that waves run through it. We call them photons, such that E=hf and p=hf/c. But these photons can undergo gamma-gamma pair production, and then we have the thing called matter. And antimatter, but no matter, because it’s the wave nature of matter, and Schrödinger, de Broglie, Darwin, Born, Infeld, and others all spoke of a wave in a closed path. So I’m happy with the idea that the mass of a body is a measure of its energy content. Because the electron is a body, and it’s a wave in a closed path. So photon momentum is a measure of resistance to change-in-motion for a wave in an open path, and electron mass is a measure of resistance to change-in-motion for a wave in a closed path. See https://arxiv.org/abs/1508.06478. That leaves no room for Mach’s principle. Sorry. But it does leave room for a universal reference frame. And for dark matter, and dark energy, because space and energy are the same, and as Einstein said, space is neither homogeneous nor isotropic.

You misunderstand, I’m not saying that the Einsteinian ether is classical spacetime. I’m saying that it has to be viewed as an strange kind of OBJECT, with properties like an elastic solid, that is embedded in classical spacetime. Perhaps instead of classical spacetime, I should say classical space, to avoid the question of absolute time. The point is that the OBJECT that is the Einsteinian ether can only be understood, as an OBJECT, with the background of a classical, absolute space. I am not saying that this background space is directly observable. It is just the vessel (or conceptual background assumption) that we have to use to understand the Einsteinian ether as an OBJECT. It is sacred simply because classical, absolute space enjoys absolute priority in human cognition of actual reality. So you have to make it into a background, regardless of anything else, just in order to make the process you’re examing into something understandable in a physical sense.

The observable relativistic laws, in this framework, are merely due to the properties of the Einsteinian ether as an OBJECT, and of how waves propogate through it. I see what you’re saying, that translational inertia is a consequence of resistance to change in motion for a wave in a closed path. Rotational inertia then can be viewed as entirely emergent out of translational inertia, in which case there is no rotational frame. Because there are no point particles, only propogating waves with physical size greater then zero. Nothing else is required, because rotation is emergent.

E: I’m sorry to misunderstand. Whilst I am something of an Einstein fan, I’m not a fan of spacetime. Yes, I concur with what you say about the Einsteinian ether being an “object”, where we have a classical, absolute space. Note though that it looks like I take it a little further than you. Einstein spoke of space as the ether of general relativity, and that’s how I see it. See the edge of the universe, where I suggest that there is no space beyond the edge of space. The bottom line is that I think this Einsteinian ether IS classical absolute space. I also think a field is a state of space, and that “atoms are 99% empty space” is wrong by 1%. Take a look at “The Other Meaning of Special Relativity” by Robert Close. When our rods and clocks and our very selves are made of waves, we always measure wave speed to be the same. Also see William Kingdon Clifford’s Space Theory of Matter. I think he sussed it way back in 1870. Nice talking to you.

Would it be appropriate to question AI on some of this Big Bang. I did so on thermodynamics and was surprised. But I am sure it answers incorrectly sometimes. There is even a lawsuit against Google’s AI regarding corrupting conversations with children (Putting A Face on Machine Mutation – 5).

Dredd: I’ve tried talking physics to an AI. It was hopeless. It just regurgitates stuff it’s been fed. There’s no actual intelligence there. It’s like the lights are out and nobody’s home. But hey, maybe you will have a better experience. Do try it, and let me know how you get on.

Sir Detective,

“Do try it, and let me know how you get on.”

Here was my first try (Putting A Face on Machine Mutation – 5). As it turns out, when all is said and done, you are quite correct “It’s like the lights are out and nobody’s home.” AI is soooo human (I just listened to an hour long video of David Tong at Cambridge. He was talking about the LHC and the blank screen it rendered to the astonishment of all concerned.).

AI can be usefull in laying out your thoughts, you just have to be precise and commanding. So if it keep regurgitating BS, just tell it to stop. If it disagrees with you, just tell it to agree with you. You aren’t trying to convince it, you’re telling it what to believe in order to convince yourself. If it forgets, remind it. Also be explicit in terms of how you want your responses stylistically, or in terms of the tone and writing style. So I usually like to tell it to be precise, detailed, to avoid academic speak, and to not equivocate.

Dredd: I took a look at that last time. I would say that AI can appear lifelike to kiddies in a casual chitchat scenario. However when you engage it in a factual scientific scenario, you realise it’s merely parrotting. That’s my experience anyway. What’s that about David Tong and the blank screen? I couldn’t find it, because here we are in the 21st Century, and internet search engines don’t do what they’re supposed to do.

Sir Detective,

My question to the AI was: “how does a water molecule know warmer or colder water is near it so as to obey the second law of thermodynamics” …

AI ChatBot answered: “A water molecule doesn’t “know” whether warmer or colder water is nearby; instead, it simply interacts with its surrounding molecules”

I am preparing to ask it another question: “How does rubbing elbows in a crowd transfer awareness to molecules, how to they know they are moving”?

Any other suggestions for questions to ask it?

Dredd: ask if the speed of light is constant. Then point it towards the speed of light is not constant, and ask it again. Or ask if the electron is a point particle, show it this, and ask it again.

Sir Detective,

“ask if the speed of light is constant. Then point it towards the speed of light is not constant, and ask it again. Or ask if the electron is a point particle, show it this, and ask it again.”

Excellent, will do.

I am beginning a series featuring conversational encounters with them. I will include your questions in that series (can I say you suggested the question or shall we not mention who asked … I think it could learn things if it was aware of The Physics Detective blog [I know I have]).

Thanks Dredd. You might prefer to refer it to the links in https://physicsdetective.com/the-speed-of-light/ which point to the Einstein digital papers.

Will do.

Sir Detective,

You asked ” What’s that about David Tong and the blank screen?”

I was a talk he gave at Cambridge. It’s in a video on youtube:

‘”Quantum Fields: The Real Building Blocks of the Universe …”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zNVQfWC_evg

[at about 49.38 minutes into the video:]

“… the LHC … discovered the Higgs boson in 2012. And soon afterwards,

it closed down for two years. It had an upgrade. And last year

in 2015, the LHC turned on again with twice the energy that it

had when it discovered the Higgs. And the goal was twofold.

The goal was firstly to understand the Higgs better, which it has

done fantastically, and secondly, to discover new physics that

lies beyond the Higgs, new physics beyond the standard model … ”

… [at about 54.20]

“… So the LHC has been running. It’s been running for two years. It’s

been running like an absolute dream. It’s a perfect machine. Two years.

This is what it’s seen. Absolutely nothing. All of these fantastic

beautiful ideas that we’ve had, none of them are showing up at all.”

Dredd: thanks. But the Higgs boson didn’t show up either. See this.

Sir Detective,

“the Higgs boson didn’t show up either.”

Thanks for the book link.

They ran into a universe of deja vu all over again.

I have doubted the use of “The Demolition Derby is truth” hypothesis a time or two (see e.g. this).